One of the projects I’m working on is simulating the patient’s cost of treatment for several types of diseases with multiple clinical pathways. We’re assuming the patient is on-Exchange and subsidized at various levels. Part of this research project means we need to categorize every single benefit design. I think I’m done with that part of the task and now I need to build a flow model. That will be my fun next week.

But as I was cleaning and organizing the data, more questions started appearing to me. I am using the Healthcare.gov QHP Landscape Public Use Files. Primary Care, specialist, Emergency Room, Inpatient Professional, Inpatient Facility, Generic prescription, Preferred Brand Prescription, Non-Preferred Prescription, and Specialty Prescription are the cost-sharing fields. Deductible and Out of Pocket Maximums for Drug and Medical are the the groupers that are in the field. I categorized a combination as unique if there was any difference in any cell. Two plans that are identical except for a $10 PCP copay that is paid before or after deductible are categorized as two unique plans.

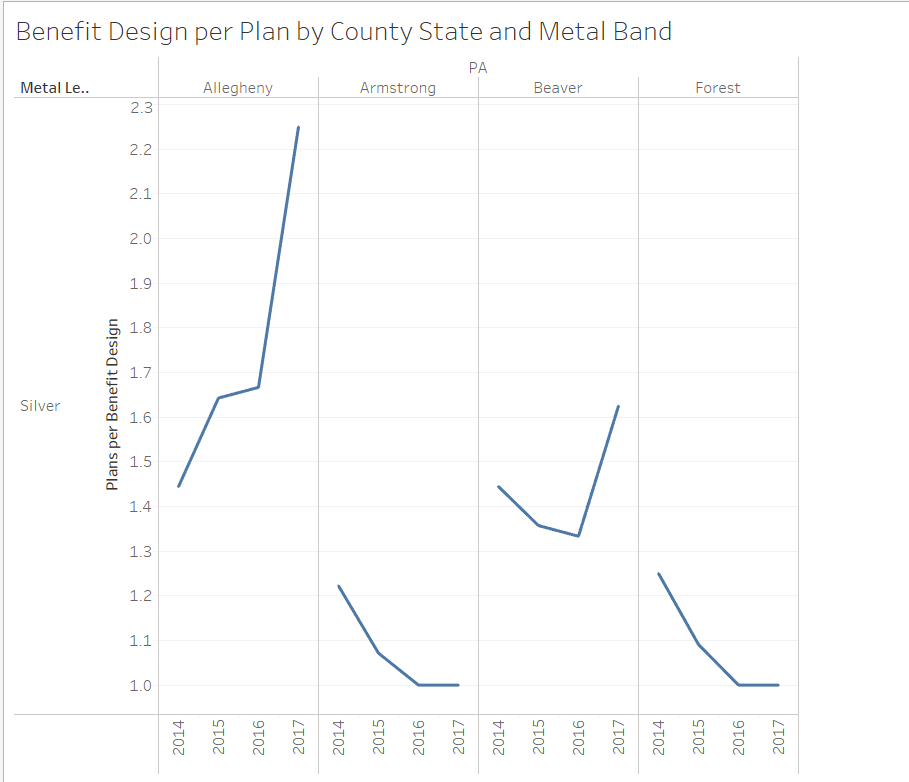

I got curious. Every Plan ID needs a benefit configuration. But many Plan IDs could share a benefit configuration. How has this changed over time? A score of 1 means every unique Plan ID has a unique benefit design. A score of 5 means on average 5 plan IDs share the same benefit design.

Below are four counties in Western Pennsylvania that I can tell the story because that was the market that I know cold. I need your help figuring out what this means from a consumer perspective.

In Allegheny County, there were a few shared benefit designs in 2014. By 2016 and especially in 2017, the same benefit design was being cloned and attached to three networks for UPMC and almost everyone else has gotten out or offered a few unique plan/benefit combinations. Armstrong and Forest County has a single carrier offering a single network and a lot of benefit designs. Beaver is an in-between case; there are multiple networks offered by the same carrier (UPMC) where the same benefit package is attached to the network.

Now what the hell does that actually mean?

I don’t know? I think the decision costs and the choice overload costs decrease as the ratio of benefit designs to plans increases but keeping track of that is hard. It is pragmatically true in Allegheny County where the UPMC Partners, Select and Premium networks all offer the same five benefit designs at a total of fifteen price points. I think it allows people to filter out the benefits as fundamentally constant and thus focus more on the price and network choices. But I’m not sure.

What does this mean to you?

narya

I think the network choices are most important (at least they are to me), but I”m not clear on how benefit designs could differ.

Cacti

I was looking for the Metal Bands.

Where’s Judas Priest?

lowercase steve

@Cacti:

::begin youtube comment-esque rant about whether Judas Priest counts as metal::

Nah, just kidding.

Major Major Major Major

@lowercase steve: it’s certainly within the n-metal manifold universe, where n is a string.

glory b

“What does this mean to you?”

That UPMC will soon take over the world (resident of Pittsburgh here)?

David Anderson

@glory b: No, when I was there, they were intent on taking over everything in Western PA with a long term plan to take over the state. The world was too ambitious

pseudonymous in nc

Perhaps one way to model it is “where is the first out-of-pocket dollar spent, for what reason, and in what month?” Is it a physician co-pay, a pharmacy co-pay, a pharmacy deductible? Does it occur in January, or much later in the year?

(Atrios is right in his post today: these choices mostly shouldn’t need to exist.)

David Anderson

@pseudonymous in nc: I’m not even trying to model this, I’m trying to scratch my head and think about it;

Does effectively standardizing on benefit design of whatever sort make it easier or harder for people to choose non-dominated and satisficing at a higher level of plan? I think that would be my research question.

StringOnAStick

I suspect standardizing on benefit design makes is easier for people to choose, but probably only because it is less confusing, not because having a range of design plans feels like a better set of choices. It just ends up being more confusing, and feeling like you are possibly sawing off the branch you are trapped on because you don’t know enough to make the right choice.

Most people don’t know enough about health care or medicine to make reasoned choices, they just want to know what any medical surprises are going to cost them and just how deep their pocket is going to have to be to survive any close encounter with the $ vacuum that is modern American medicine.

KithKanan

@David Anderson: I think it will matter if the exchange makes it easy for people to understand which plans have the same benefit design and what the real differences between them are.

If not, every additional plan will just add one more choice and additional confusion given how confused people already are about insurance.

EhtylEster

re:

That’s pretty much what i think whenever i read your health insurance posts.

mai naem mobile

Benefit design complexity – I saw the header and I thought it was Dolt 45s lack of complexity in thinking of the benefits of dropping a MOAB design bomb right before he hits his 100 days in office mark.

pseudonymous in nc

@StringOnAStick:

I agree with this. My point about first-dollar usage is that people make choices based upon headline numbers tied to expected health needs, and also assume that there’ll be something they overlooked that will show up to bite them on the rear.

Consider pharmacy formularies, where tiering and preferred brand choices for non-generics can substantially change the benefit from year to year while the headline co-pay numbers remain the same across plans. There’s no conceivable way that even the smartest policy buyer who checks that every provider and facility is in-network can do due diligence on the formulary, because you can be tied to a specific device/consumable ecosystem, and also not know what you’re going to be prescribed six months from now if your current prescription stops working. (A specific example: an Exchange plan formulary that only covers one brand of glucose test strips, which has the knock-on effect of making integrated meter/pump setups for T1 diabetics much less functional.)

pseudonymous in nc

One other thing I’ve noticed on multi-tiered Exchange formularies is what you could call the “prices start at…” effect: lots of generics are now Tier 2, and Tier 1 only applies for a handful of drugs: generic antibiotics and steroids and so on.

The pharma-PBM-insurer setup is as dirty as the NCAA, and changing that is a matter of public policy, but year-on-year consistency with the formulary and perceived portability of the formulary is a big part of what counts as a comparable benefit.