Mauna Kea, to be precise — several times. I’ve shot parts of three films there, all centered on the telescopes atop the highest mountain on the Big Island of Hawai’i. As you may have noticed, the mountain — and a new telescope — have been in the news lately:

Construction was set to begin this week on a giant telescope on the barren summit of Mauna Kea, a volcano on Hawaii’s Big Island, considered the best observatory site in the Northern Hemisphere.

That would be the Thirty Meter Telescope, or TMT, a project that originated with the same team that built the twin ten meter Keck telescopes that were the largest optical telescopes in the world from 1993 to 2009. (They’ve since been pipped by the Gran Telescopio Canarias (GTC), atop the Canary Islands.) Astronomers and designers from Caltech and the University of California system, later joined by other partners set out to build the TMT as one of the next generation of ‘scopes aiming to explore some of the fundamental questions of astronomy, many of which were raised by discoveries made by the current generation of ginormous light buckets. That would be stuff like deeper investigations of the large scale structure of the cosmos, maybe image of planet formation around distant stars, certainly black hole inquiry and much more.

The TMT project was launched with great confidence. The problems its leaders anticipated were technical: how to construct an light-gathering area and/or an optical pipeline that large that holds its shape, that doesn’t mind temperature shifts, that can be morphed on demand to adjust for turbulence in the air above it and so on, through a whole host of very tricking engineering issues.

But there was never any real doubt about the right place to put this instrument, or of the project’s access to the summit of Mauna Kea, which, after all, already played host to more than a dozen other observatories. (I know this, because I talked to those in charge of the project at the time of its inception, many of whom had appeared in one or another of my films.)

They were wrong. Last week, after years of delays, some negotiations, and, by now, mistrust and more on the Hawai’ian activist side, the state governor announced that the project had cleared its last hurdles and construction would begin. This week, protestors blocked the one access road to the summit and the observatories brought their people off the mountain. At first, law enforcement was on the scene, but there were no direct confrontations. That changed yesterday:

On Wednesday, that opposition had a new face: About 30 Hawaiian elders were arrested as they blocked a road leading to Mauna Kea’s summit to halt the construction, organizers said. They described an emotional but peaceful scene as the elders, who were sitting under tents on the road, were escorted by police officers to nearby white vans while dozens of other protesters chanted and cried. Some had to be carried.

“We have come to the point in time where enough is enough,” Leilani Kaapuni, one of the elders, said in a phone interview. She said she was arrested for obstruction of a government road but later returned to the blockade. “This mountain is sacred,” she said.

If I had to guess, I’d expect this to end in a loss for the protests. There’s a lot of momentum behind the TMT, and a ton of money involved — and there’s a huge investment in cash and intellectual possibilities in the existing observatories that would probably be lost if the new instrument didn’t make it to the mountain. Money and power talk, so I’d bet the Hawai’ian state authorities will muscle this through — and likely with the support of plenty of citizens of the state (though I’d bet many fewer among those Hawai’ians of original Hawai’ian descent).

Visible protest against the telescopes will be much more difficult if/when the TMT goes in, as the almost all the action of high altitude astronomy now takes place far from its mountain tops. The Mauna Kea observatories have the headquarters well away from the summit. Those astronomers doing science with the telescope, if they aren’t looking at a truly remote feed back to their offices back home, get no closer than the cattle town of Waimea, miles away and more than 10,000 feet in vertical distance away from anything a mere observer could break.

Those using the TMT wouldn’t see, that is, the kinds of protests going on now. And the question of who has power over sacred spaces of interest to the dominant culture will be answered again, in the same way it has been almost every time these conflicts come up.

I should say that I’m an astronomy lover. I find the science that the TMT could do to be fascinating and utterly beautiful. But man-o-man, have the leaders of that project botched this dispute for years. I do not know how you now get this project i any way that acknowledges and accommodates the claims of the disempowered first residents of the island. But I do know that failure will have consequences; human goods — which scientific discoveries certainly are — achieved by the destruction of other goods are tainted.

I’ll leave you with the text of an article I wrote for The Boston Globe on this same subject four years ago. Looking back, I can’t say I’m surprised that the astronomical community didn’t find a way to connect to its opposition. But I am saddened by that fact.

Images: Johannes Vermeer, The Astronomer, c. 1668

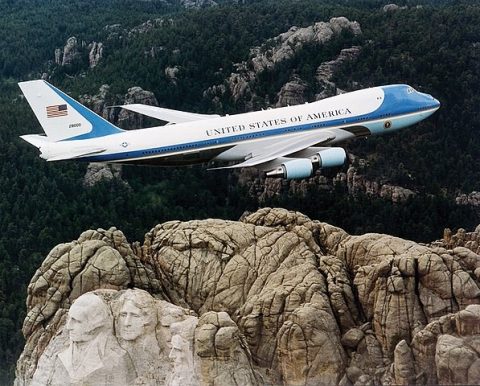

US Air Force file photo, Air Force 1 over Mt. Rushmore, 10 February 2001.

AT 13,796 FEET, Mauna Kea on the Big Island of Hawaii is the tallest point in the Pacific Ocean. It’s a confounding place. Like the Grand Canyon, it takes a surprising amount of time simply to believe your eyes. The summit and the valley immediately below the top are barren stretches of red-black rock. It’s hard not to think of Mars.

But then — at least for me, on my first visit in 1991 — the view opens up. Look north across the strait between the Big Island and Maui and there’s Haleakala, the next giant volcano in the chain. To the south, Mauna Kea’s twin, Mauna Loa, bulks across half the sky. West, past the golf courses and beach hotels of the Kohala coast, there’s nothing but the broad Pacific — on a clear day, a sheet of utterly, impossibly cobalt blue stretching to the edge of the earth.

No mere photograph prepares you for first sight on Mauna Kea. For me, the experience was shot through with two truths: how almost impossibly small each of us is within the natural world — and how utterly interconnected that world is, to itself and to each infinitesimal self peering though it.

Look at the peak rather than from it, though, and the scene shifts. Mauna Kea possesses a unique combination of attributes: usually clear skies, high altitude, stable air, almost no light pollution. The first astronomical observatory appeared on the mountaintop in 1970, a gleaming white dome visible for miles. In the 45 years since, the near-perfect observing conditions have brought a flock of telescopes to land on and just below the summit ridge, 13 in all, including the two largest optical instruments now in use.

Astronomers are not the only ones to prize Mauna Kea, however. The mountain is sacred within the native Hawaiian tradition, a home for gods and the junction between the earth and the sky. There are ancient burial sites, and more than 140 shrines have been found so far. To this day, the mountain remains a focus of Hawaiian spiritual practice.

Even so, for most of the last half century, the observatory complex has expanded in the face of only seemingly minor objections from local communities. But Mauna Kea’s proposed 14th telescope has changed all that.

The dispute over the Thirty Meter Telescope — the TMT — has been simmering for some time, but it finally came to wider media attention on April 2, when a dozen activists were arrested for blocking construction crews below the summit. Work at the building site has since been suspended, and the protest movement has spread, perhaps most significantly, into social media. Last week, Hawaii’s governor endorsed construction of the TMT, with the caveat that 25 percent of the existing telescopes on the site be removed.

Perhaps inevitably, the dispute has been framed as the latest skirmish in the long-running campaign pitting science against religion. That’s a mistake, one that makes it nearly impossible to find a way to speak about what’s at stake in a way that makes sense to both sides.

FOR THE LAST century, each leap in telescope diameter has generated exceptional discoveries, from finding out that our universe is expanding (and hence has a history and an origin) to the recent revelation — spurred by observations made on the Hubble Space Telescope and the largest land-based optical instruments — that three-quarters of the universe is made of a mysterious phenomenon called dark energy.

The TMT’s builders expect similar discoveries. With a primary mirror that’s nearly 100 feet across, its “light bucket” has nine times the area of the largest optical and near-infrared telescopes now in use. That will throw open a new window into the “dark ages” of the early universe, when the first stars formed. The TMT will track how the cosmos evolved its structure, look into the mystery of dark matter, pursue giant black holes as far into the past as possible, study the formation of planets around distant stars, and much more. As the TMT organization puts it, “It is very likely that the scientific impact of TMT will go far beyond what we envision today.”

In the face of such grand ambition, the protests took supporters by surprise. George Johnson, writing in The New York Times after an earlier protest in late 2014, declared that the TMT will be “a triumph in astronomy’s quest to understand the origin of everything,” and that the protesters are indistinguishable from “religious fundamentalists who are still waging skirmishes against science.”

Retired University of California astronomer Sandra Faber was even more blunt. She wrote an e-mail intended to gain support for a petition defending the TMT. A colleague circulated it more widely, which is how this passage became public: “the Thirty-Meter Telescope is in trouble, attacked by a horde of native Hawaiians who are lying about the impact of the project on the mountain. . .”

The use of the words “native” and “horde” had the impact one might expect: Here were senior astronomers, leaders of the field, calling their opponents a mob — with the overtones the word “horde” brings of savagery, the maddened rage of the unenlightened. This was the language of outraged power, to whom opposition is not just an obstacle, but an insult.

Faber and her colleagues have apologized — but plenty of cheerleaders for science agreed with the underlying message: This is a battle between a universal good and the mere belief of a handful of ignorable people. Physicist and storyteller Ben Lillie wrote an influential essay for Slate in which he placed the Hawaiian conflict in the context of historical misdeeds committed by or through science. The comment thread provided its usual glimpse of the id of those who disagreed. Among the more measured responses: “Sacred, schmacred. . . . It’s a big rock with room on top for some cool science stuff.

End of discussion” [ellipsis in the original]. And “At some point common interest has to overrule religious ‘rights.’ ”

To the opponents of the TMT, of course, Mauna Kea is hardly a “big rock.” Within Hawaiian tradition, Mauna Kea contains multitudes. Keolu Fox, a geneticist of Hawaiian descent writes that the mountain “is sacred to the Hawaiian people because it represents the beginning of our oral history.” In traditional Hawaiian society, the summit was forbidden to all but the highest ranks.

Now Mauna Kea serves as a focus and spiritual sanctuary for Hawaiians seeking to preserve and extend their cultural heritage. Ruth Aloua, who helped block the summit road during a protest in March told the Hawaii Tribune-Herald that “We have an ancestral, a genealogical relationship to this place,” adding “that is what we are protecting.”

SCIENCE IS UNIVERSAL. Its methods, practices, and results are the same everywhere, reproducible anywhere, accessible to anyone. Isaac Newton found that force equals mass times acceleration, and F=ma is as true in Beijing or Capetown as it is in Boston — or atop Mauna Kea.

Science is a good, essential to human well-being. The machine on which I write this, the fact that nearly all babies born in the United States make it to their 5th birthdays, that the world produces (if it does not always distribute effectively) all the food 7 billion people need to survive — all this and so much more derives from the fact that reason, mathematics, and rigorous experiment confer power over the material world. (As, of course, does the technology of modern war; what people do with knowledge is never an unmixed boon.)

But while a conventional and valid defense of basic science is that we have to do it because that’s where the next generation’s inventions are born, most researchers would argue that there’s more to their calling than useful mastery of nature. Robert Wilson, a physicist and founding director of Fermilab, was once asked if his giant atom smasher would make the United States more secure. No, he told a congressional committee, “It has nothing to do directly with defending our country except to make it worth defending.”

That was a grand way of saying that there are human needs beyond the merely practical. Researchers talk of their hunger for deep answers, or the rewards of elegance and beauty. Here’s Albert Einstein: “Out yonder there was this huge world which exists independently of us human beings. . . . The contemplation of this world beckoned like a liberation, and I soon noticed that many a man whom I had learned to esteem and to admire had found inner freedom and security in devoted occupation with it.”

ASTRONOMY WAS ONCE supremely practical. Decisions about marriage, the planting of crops, or whether to go to war were all once decided by the stars.

Problems of navigation occupied professional astronomers well into the 19th century. Not any more. None of the deep space telescopes that humankind has placed on mountaintops since the beginning of the 20th century serves any immediately useful function beyond Einstein’s contemplation of this huge world.

Just look at the TMT’s goals: to reach back to the epoch of the first stars, to search for new planets and nascent stellar systems, to dissect the mysteries of exotic forms of matter. None of these have anything to do with the price of eggs. These are fundamental questions. The contemplation of them requires instruments like the TMT. Doing so offers liberation, an escape from the mundane, a kind of transcendence.

If that sounds familiar, it should. That’s the same promise that many forms of religious practice offer. And it’s recognizably similar to what the Mauna Kea protesters say they seek to defend.

I do not make here the old bad argument that religion and science are basically the same, just two ways of knowing. They’re not. Science creates knowledge of material experience that cannot be produced by any other means. Its measurements, methods, and results are indeed common property as no particular religious commitment can be.

But the TMT dispute shows where the science versus religion trope goes wrong. The Hawaiian protesters haven’t said that Mauna Kea’s telescopes are inherently impious, or that the data they collect is somehow wrong, or that Hawaiian mythology is a better account of the cosmos. Rather, the value, the joy, the need the observatories satisfy may indeed satisfy many, but not those continuing a Hawaiian tradition that allows its heirs to find connection with memory, with history, with nature — to achieve the same transcendence sought by those who find beauty in the measure of the universe.

That is: The TMT defenders and their opponents seek analogous rewards from their presence on Mauna Kea. Their conflict isn’t between the competing worldviews of science and religion, but between desires that are kin to each other — and that require the same physical space.

LANGUAGE MATTERS. Finding a common way to express what’s at stake is an essential element in any negotiation, in any dispute. Most important, if one side has more power than the other in a conflict, finding a way to make those more powerful hear what the opposing side is saying is both vital and exceptionally difficult.

A personal note: I love astronomy. I have felt joy every time I’ve made it up to Mauna Kea’s observatories. I’m not sure that human beings have ever made more beautiful images than the Hubble Deep Fields. I do hope the TMT project continues, and that from first light it reveals something unimagined. I once made a film about great observatories called “Cathedrals of the Sky” — and that’s what the TMT is to me, a domed source of wonder, a conduit to Einstein’s huge world, independent of mere individual human concerns.

But as long as those on Team Science assert — and believe — that what they do is universally valuable, trumping any merely local claim, then the Hawaiian dispute is merely an annoyance to be managed. That’s an argument that cannot be resolved, cannot end. Should it become possible to hear what the other side wants in the same form as what the astronomical community values, then there’s something to talk about, and a way to do so. It may require a bit of uncomfortable modesty from science — it won’t be easy to accept that the beauty of pure research competes with other approaches to connection with the wide world — but the results of speaking a common language may surprise some telescope advocates.

That alone won’t solve the critical question, of course. Hearing — genuinely engaging with the idea — that astronomical observation and spiritual practice on Mauna Kea as are matched responses to the same emotional impulse does not in itself make an argument for or against building the TMT. But seeing it that way it is a key step in the discussion that needs take place now.

debbie

Sigh. No one seems to see the bigger picture any more.

Parmenides

Whatever on the back end has broken the site for Chrome. For a while I was getting a DNS error and now the formatting isn’t working. Just letting your know. I’m running minimal extensions Just HTTPS everwhere and Ublock, which appears to be the problem.

Mary G

Great article, Tom. Language and paying attention are crucial, and it sounds like the proponents of the telescope have dropped that ball. Unfortunately, it seems like the usual will happen and the brown people will lose. Protecting religion only applies to white people in a narrow form of Christianity.

Raven

mauna kea from mount haleakala cinder cones

debbie

@Raven:

Beautiful in an otherworldly kind of way.

Jerzy Russian

I think the TMT’s backup plan is to go to the Canary Islands. That would be a huge loss for Hawaii and the United States in general.

Cermet

I find all religious arguments both silly and based on utter fantasy of the worst sorts; that said, I can understand their justified anger after the promise, some years ago made to them, that there would be a limited number of scopes (far fewer than currently up there) – all parties were satisfied with that arrangement when it was made. Surprise – utterly broken and many more scopes have been placed upon the summit. Here I have to say that the original agreement MUST be honored both as law and principle. If they want another scope, others (at least two to prove their heading to the far lower number that originally was agreed upon) must be removed and those areas returned to a more natural state within reason. Otherwise, what is the point of law if money always trumps it?

Tom Levenson

@Raven: Hah! I’ve taken the reverse shot, in still and moving images.

Martin

The problem I have with this is that you wind up with these projects that get out of phase with the politics on the ground. This project started in 2000. 19 years ago, and first light is planned for 2027, 8 years from now. That’s a long fucking time. Too long. And you suffer then from two problems:

1) What was reasonable 19 years ago may not be reasonable now.

2) After 19 years of planning, your sunk costs are so high you can’t compromise or change course.

These projects need to operate much faster. We got to the moon in 7 years. It shouldn’t take 27 just to look at the moon. I’m entirely familiar with how these things are funded and organized. My specialty is astrophysics so I’m certainly sympathetic to the benefits of these projects and how they come about, but this is also a process that ends up being riskier due to it’s massive risk aversion. It’s why so many large projects run so long, and so over budget. They need a different approach.

Oh, and I do have a solution. Build it on Everest. Even better optics, and you can prevent all of those idiots from dying just in order to get a selfie by putting a proper road up to the summit.

Tom Levenson

@Cermet: a) there’s more to religious arguments than magical thinking and supernaturalism. History, connection to place and the flow of time, and, simply an assertion of some authority over places that played specific roles in the culture they still claim are all in play. So I think (as I wrote in 2015) I don’t think the religion v. science wrestling match is a great way to go.

They have removed some telescopes from the summit, and I think plan to do more. (I haven’t kept up, but I believe a couple of the very small scopes are gone, and probably the old University of Hawai’i instrument. Maybe some others.) Another issue, beyond the observatories themselves, has been just a general carelessness on the mountain top, which collides with the preservation of shrines and such like. One thing that isn’t being reported and I haven’t followed up on is how representative the folks on the mountain are of the views of Hawai’ian origin folks more generally. There was some divergence of opinion a few years ago — but I wouldn’t be at all surprised if general fuckery had coalesced views against the TMT among folks who were more inclined to come to an accommodation earlier. But I haven’t done the reporting to be sure of anything.

CaseyL

@Martin:

Oh, that’ll go over well with the Nepalese and Sherpa families!

Jerzy Russian

@Martin: Well, if you had a President announce that it was the goal of the country to build a big ass telescope, and the whole country put their full effort into the project, then the telescope would have been built much faster. As it was, there was a lot of time spent on find raising, being challenged in court, etc.

Parmenides

I’m also getting DNS_PROBE_FINISHED_NXDOMAIN error on multiple sites so it may be a wordpress issue.

Mary G

@Parmenides: Yeah, because it’s been working fine for me on Chrome all week while everybody complains.

ETA: I don’t use extensions or apps.

Aleta

good article

Cacti

I predict the interlopers with the money will win.

Yutsano

@Cacti: Oh yeah, eventually. The history of moneyed interests getting their way over native Hawai’ian wants/needs is pretty much the colonial history of the islands. AKA why the monarchy is little more than an asterisk now.

Tom Levenson

@Yutsano: I couldn’t believe the on-the-noseness of the Mt. Rushmore photo when I found that, punctuating your point.

dmsilev

@Martin:

Actually no. There’s too much turbulence in the air rushing over the Himalayas. The alternative site for TMT is/was the Canary Islands. As I understand it, purely from an astronomical quality perspective, Mauna Kea is somewhat better but not leaps and bounds so. There’s enough sunk costs into the details of the Hawaiian site design at this point that there’s a lot of reluctance to write that off and move the telescope. Not saying it won’t happen, but especially now that the Hawaiian Supreme Court has weighed in along with everyone else, I’d say it’s unlikely.

Tom Levenson

@dmsilev: Yup. Again, there are plenty in the state who very much want this to happen, for simple reasons — the money, the ongoing spending such installations evoke — and for many of the same ones that animate astronomers who want to use the telescope. And the legal system offers a way for those with the skill to use it to set the terms of action. In some ways, the question has long been do the telescope proponents get their way by overwhelming force, or by some more consensual process. We’re about to see the answer.

Tom Levenson

@dmsilev: @Tom Levenson: Also, re the Canaries — I haven’t talked to the TMT people for a while, but one of the original attractions of Hawai’i, beyond the simple excellence of the site, was that there was already a well established astronomy infrastructure, with lots of trained people, colleagues to talk to, in an English speaking location that used the US $ and didn’t require clearing customs to get there. Some of that becomes less important with the rise of remote observing, but not all of it.

dmsilev

@Tom Levenson: Another complexification is that TMT is a consortium and there are internal politics at play for any sort of big decision like “do we move the whole damn thing halfway around the world or do we push harder to make this one work?”.

Jerzy Russian

@Tom Levenson: There is plenty of astronomy infrastructure on the island of La Palma. Not sure how much room is left on the main summit though.

PsiFighter37

Flying out to see Mt. Rushmore this weekend. Looks like the weather will (thankfully) cool off, and it should be mostly clear skies while I’m there. Also excited to see the Badlands as well.

Tom Levenson

@Jerzy Russian: yes, but as the site selection process was underway, that was less true.

Mary G

More assholery (now behind a paywall, but should be on regular Politico tomorrow for us peons.) Trump to close all refugee programs.

JDM

Some years ago I was at an anthropology conference where, for what may have been the first time, physical anthropologists and natives met together at a conference to discuss repatriation of skeletal materials. Interestingly, the native side was quite open to suggestions about how to handle the subject in a way that both they and anthropologists would find acceptable. The anthropologists there were virtually all entirely unwilling to consider anything; they were there, apparently, just to lecture natives about why having their old cemeteries dug up and stuffed in museum drawers was a non-issue.

I was married to an anthropologist and went to a lot of conferences; I was predisposed to be on their side but they were, at that time at least, just being jerks.

The oldest member of the native contingent pointed out that they really didn’t want this to be decided by courts; that they’d rather, much rather, work with the anthropological community. But he also pointed out that the USA promises freedom of religion, but doesn’t promise freedom of science.

?BillinGlendaleCA

@PsiFighter37: The kid is thinking of seeing that and Yellowstone on one of her adventures.

NotMax

Should be noted that one of the conditions agreed to and imposed on building the TMT is the removal of three other extant observatories atop Mauna Kea. So if there are 13 now, after TMT and this associated condition, there will be 11.

Steeplejack

@Mary G:

One thing I have noticed lately is how completely—unless I have missed something—Trump has stopped talking about “the wall.” Did he even mention it in his rally last night?

They appear to have moved on to “What are other ways that we can screw with immigrants and asylum-seekers?”

NotMax

@Steeplejack

Yes, he mentioned (read: lied about) it.

Steeplejack

@NotMax:

What did he say?

Mary G

@Steeplejack: I’ve seen passing references to it’s already been started still, but yes, I think he’s moved on because of the horrors they are still committing down there. This whole attack on the “Squad” is to distract from the border.

Roger Moore

@Martin:

I’m not certain the optics will actually be better. It’s not just thin air that makes a good site for an observatory. If any tall mountain with a road to the top would do, there would be big a big observatory on Pike’s Peak. You want air that’s free from turbulence. Islands are good for that because the ocean acts as a big heat sink so you don’t get turbulence from difference in air temperature. Mt. Wilson, here in Southern California, is still considered a good site for astronomy* because the same inversions that cause problems with smog in LA make for still air and good viewing conditions above the inversion layer. Not to mention the construction and maintenance problems with trying to build anything at an elevation where people need oxygen tanks to survive.

*At least for the kinds of astronomy that aren’t bothered by light pollution.

NotMax

@Steeplejack

I’d have to go back and look it up – or worse, listen to him. Shall take a hard pass.

Yutsano

@Steeplejack: The Wall was mentioned (I believe) as “being built right now” but the audience has a bigger hit for their racist rush now. “Send Her Home” is the new hotness in that crowd.

low-tech cyclist

@PsiFighter37: Mt. Rushmore up close looks exactly like the pictures. The Badlands are kinda cool, though. And Jewel Cave and Wind Cave are definitely worth seeing – the best part of the Black Hills is underground.

Another Scott

@low-tech cyclist: As is the Mammoth Site.

Cheers,

Scott.

NotMax

Side note on the Law of Unintended Consequences.

One of the structures atop Haleakala here on Maui was built with a reflective exterior, meant to “blend in” with the sky and terrain. (IIRC it is the solar observatory.) Most of the time the building is an ultra-bright beacon when seen from afar, reflecting sunlight..

Raven

@Yutsano: I’m sure we all understand by now that their primary goal is to fuck with libitards. The more horrified the better.

Raven

@NotMax: It was pretty visible at sunrise!

Martin

@Jerzy Russian: No, I get that, but these are invariably monolithic projects which never, ever, ever scale well. For instance, Mauna Kea has 13 telescopes. One of the better arguments for ground vs space telescopes is that ground based can be upgraded and maintained vastly more easily. That’s a good argument. So, why not build a set number of visible/infrared/radio telescope foundations and upgrade them, rather than continually adding to set? You reduce or eliminate the challenges around securing new land, by reusing land. You have an existing foundation to build on. And odds are you can get the project from start to end VASTLY faster than the current process. And once you’ve established infrastructure, you start your design around that infrastructure – reusing as much as you can, and replacing what you can’t.

But that means convincing someone to give up their telescope, or inviting them in to your consortium and thereby diluting your own utilization. Honest to god, this is scientific rent-seeking. I’m sympathetic to the scientific goal here, and I’m sympathetic to the parties building this because I’m employed by one of them, but I see this pattern over and over and over and it’s infuriating. It’s a similar pattern that led to healthcare.govs failures, and SLS, and so on. There is something really busted with how we go about large projects here in the US that prevents us from pricing in these risks and prevents us from seeking any kind of collective benefit.

HinTN

@Raven: Haleakala is an inspirational place. Beautiful photograph. Thanks

Mike in NC

Several years ago I climbed to the top of Diamond Head. They were selling certificates inside for $5 but I had no cash on me.

NotMax

@Raven

Was slightly mistaken, I think. The super reflective silvery one is the AEOS. Different shot.

Roger Moore

@Martin:

The main reason is that the old telescope foundation probably won’t support the new telescope. The telescopes that are being replaced by the 30 meter telescope are all in the 3 meter range. Yes, you could theoretically upgrade their existing foundations for the new scope, but it would be like one of those home “renovations” where they tear down everything but one wall to preserve the fiction that it’s not a completely new house.

Omnes Omnibus

@Mike in NC: Well, you either climbed it or you didn’t. If you did, then you know and you don’t need a certificate. If you didn’t, then you also know and no certificate will change that.

NotMax

@HinTN

Some more stunning views. #1 – #2

dmsilev

@Martin:

You’d end up replacing practically everything, including the foundation, and just reuse the land. A telescope built today is substantially more demanding in its site requirements than one built 20 or 30 years ago, and I have to imagine that whatever gets designed when TMT is reaching its sell-by date will be even more demanding (assuming, of course, that we haven’t just relocated everything to the Earth-Sun L4 point or whatever). And reusing the land is exactly what TMT is doing; a few older and smaller scopes will be decommissioned as part of the construction project.

Another Scott

@Martin:

Maybe I’m misreading you, but I’m surprised you’re making this argument.

Not all astronomy can be done like the VLA.

Technology marches on. And new technology has new requirements and enables new science. Deformable mirror adaptive optics only started in the 1970s, when the idea of actually making a 30 meter telescope was as fantastical as the idea of DNA editing or using Majorana fermions in real computational circuits. Who knows what new technologies will be available in the next 50 years. (The 200-inch (5 m) Hale telescope from 1948 was one of the largest in the world until 1993.)

The cost of the site isn’t in getting the permits or building the footers for the foundation. It’s in all the design work, the time and development costs in waiting for essential new technologies to be perfected, etc., etc.

And I don’t see how making a telescope park for a dozen new, say, 50 meter telescopes is going to make the political and social issues any easier. There’s still the fact that if the mountain is used for giant projects then it’s not being reserved as a sacred place. That fundamental conflict can only be mitigated, not totally resolved, and only with good will on all sides.

“Why should we give you money for your breakthrough new-physics telescope when we spent a bunch of money for all those old-style telescope facilities that you’ve never used??”

My $0.02.

Cheers,

Scott.

HinTN

@NotMax: I get a “bad gateway” error on #1. #2 is nice. I was there in winter 1987 in the early morning. I’ll never forget it.

HinTN

@Another Scott: We all could use a lot of work on that which Aretha pointed out a short while ago: RESPECT

Lee Hartmann

@Roger Moore: You can’t build it up on Everest, Far too high. If it is dangerous when too many hikers get up there, imagine getting heavy equipment up there, people working with no breathable oscygen, etc. The highest atronomy site is now Atacama, and that is difficult enough(15,000 ft) but it is a flat area, with reasonable access for heavy equipment, and extremely dry.

Gin & Tonic

@Omnes Omnibus: A long time ago I made a corny photo, now lost, of one of those “This Car Climbed Mt. Washington” bumper stickers next to a pretty worn pair of my hiking boots, which were the “car” for me. No longer have any of those items.

Schmendrick

I normally come here as a consumer of the thoughtful writing I consistently find here. I rarely comment because (a) it is much more work; and (b) I am not sure my writing is up to the usual high standards here. But today Tom’s article about the TMT struck a chord and I am emboldened to share a bit of my personal history.

For about 30 years after college I worked in various parts of the world in the defense/aerospace industry. A few years in Europe, a few years in Hawai’i and various locations in the USA mainland. As i approached my planned retirement age of 55 I discovered that my employer had a contract to support several of the telescopes on top of Haleakala. Since my wife and i both enjoyed our time in Hawai’i, it occurred to me that this would be a great way to finish out my career.

Unfortunately for me, my background and experience was mainly in radar and other “non-optical” areas, so I was really not a very good fit. As it happened, there was a position open at the observatory in Albuquerque which I applied for. It seemed like an excellent opportunity for me to get my foot in the “optical” door (so-to-speak) with the idea that I might then be qualified to transfer to Maui. After my interview I was informed that I was the second best candidate, but a few weeks later I learned that he had changed his mind and turned down the position and that is how I came to spend my last 18 months of my career at the Starfire Optical Range. Although I did not achieve my goal of a career ending assignment in Hawai’i, I discovered what a religious experience astronomy can be, and I also discovered that Albuquerque is a wonderful place to live.

Some days I am optimistic that people of good faith can find a way to cooperate to resolve conflicts like this in a way that reflects thoughtful compromise, especially when I read articles like this. Then i remember which timeline I am in.

Another Scott

@Schmendrick: Great post. Comment more often. :-)

Cheers,

Scott.

Tom Levenson

@Schmendrick: @Another Scott: seconded.

a lurker

Long lurker crawling out here, since this is happening in my backyard. I was born and grew up here in the islands, and although I left for a long time, I did return. As with most things, there is a lot going on below the surface that you need some local background to start to fully appreciate. Obviously, an important piece of this is the whole colonial history of Hawaii. The TLDR Cliffs Notes version is: Rich White Guys overthrow indigenous monarchy. Rich White Guys import lots of disparate immigrant groups to do labor and play the groups off of each other to maintain power. Eventually labour unions get different ethnic groups organized as workers and seize control of state politics. As unions became less powerful, things have become more factionalized, but there is no single group that has anything close to a solid plurality, much less a majority. I feel like we’re much closer to a “Class Not Race” politics here than anywhere else I’ve been in the US.

The Kanaka Maoli (indigenous Hawaiians) were obviously mistreated and ignored by successive governments in various ways. In addition, there are large Trusts that were established out of the estates of the Hawaiian aristocracy, as well as the Office of Hawaiian Affairs, a government bureaucracy, that were established specifically for the benefit of the native population. These organizations are, by far, the biggest private landowners in the state. They also have a long history of egregious corruption and mismanagement. Needless to say, the issues that the native community has with the government and the institutions set up to benefit them are varied, real, and justified.

As far as economics, the island was up until 30 years ago dominated by cattle ranching and sugar cane plantations. The sugar cane plantations all went bankrupt by 1990, and nothing has really come along to replace them. The biggest economic drivers are tourism and government jobs. Tourism provides mostly shit jobs, so there is a lot of interest in trying to get some sort of other industry off the ground, but not very many viable plans in that regard. Basically any proposal here to build anything new or different gets hit with both your standard issue NIMBY objections, and on top of that, as in this case, there are state constitutional rights of native Hawaiians to access resources needed for traditional cultural practices.

A fairly common view around here is that the astronomical resources are one of the few unique things about the island that can sustain non-tourism-related jobs and where the extra costs associated with everything on remote islands doesn’t ruin the business plan. I find myself conflicted, because I recognize the arguments made by the kanaka regarding the importance of the mountain to their culture and religion are valid. However, I am also of the view that the island would greatly benefit in many ways from having a dynamic and growing observatory on the mountain. As far as an industry goes, I can’t imagine very much that would bring as much to the island while asking for less in terms of land and environmental footprint. Plus, I think the observatories are hella cool. Growing up here, those bright white buildings on the summit were one of the few things in this sleepy rural locale that made me think that this place was interesting and made a contribution to the modern world. I don’t think that those things are necessarily in conflict. But history suggests that the natives should probably not trust any promises that the government negotiates with them.

I guess I think that it’s important and right for those Kanaka who think this is important to protest against this. I should add at this point, that this is not a universal point of view in the native community, there are plenty of native agnostics and TMT supporters, although they tend not to be very vocal about it. It’s right that opponents challenged the permits and process. It’s also probably right that they lost the legal arguments. I guess we’re currently at the stage where they engage in civil disobedience because it’s that important to them. That’s also correct. I just hope at this point that the state can find a way to resolve the issue and allow everyone to move on with a mix of pride and disappointment and without siccing the riot cops on the crowd.

Another Scott

@a lurker: Thanks very much.

Cheers,

Scott.

Marshall Eubanks

Things may not changed as much as the poster thinks, as much of astronomy has very practical uses.

The big telescopes on Haleakala are mostly used to hunt for asteroids – that is to say, for planetary defense, which strikes me as an “immediately useful function.” And the Mauna Kea radio telescope is part of the VLBA, which is used (among many other things) for navigational support, such as by extending the celestial reference frame (this amounts to 1/2 of its current funding). The radio telescopes up on top of Waimea in Kauai are used directly for navigation updates for the Global Positioning System and its GNSS brethern (that accounts for basically all of their funding).

Marshall Eubanks

When I was in charge of building a radio telescope on Waimea we made sure that the local community was consulted and was reasonably happy. I paid for the blessing of the telescope out of my own funds…

DaveLHI

Tom, there’s a lot that’s right in what you’ve written here, but also a lot that’s wrong, starting with the idea that TMT didn’t plan for opposition and hasn’t tried to understand the perspectives of opponents. They’ve been working with the community for 10 years, supporting educational programs and reaching out. The existing Maunakea astronomy community is deeply embedded in the Big Island community and doing the same and more. I have my quibbles with TMT’s community efforts, but it’s just wrong to suppose that Sandy Faber’s comment from five years ago is anything like representative of the TMT project, much less current Hawaii astronomy. What we didn’t see coming was the way that Maunakea and TMT have become a rallying point for the sovereignty movement. That’s mostly recent and deeply sad. If you have the time and the inclination to work on this again, I’d be glad to put you in touch with people who can help.

(Long time lurker, infrequent commenter.)