Buying health insurance on the ACA marketplaces is tough. It is tough under the best of situations as it involves, for most people, a lot of probabilities and estimates of future likelihoods and unknowns with little certainty. It is tougher when attention span is spammed and hacked.

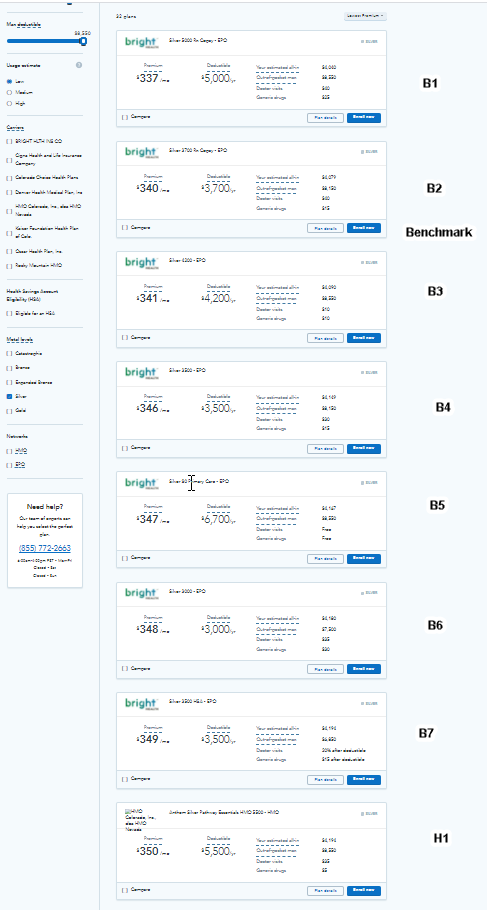

I was looking at the offerings in Denver, Colorado last night for a quick check on another topic, but I saw the following on the first page of silver plans:

There are a total of 41 silver plans being offered in Denver County.

Bright Health Plan offers the cheapest silver. They also offer the benchmark, second least expensive silver plan. And then they offer another 5 plans before the first plan offered by another insurer.

The plans being offered by Bright are extremely similar to each other. There is a little bit of wiggle room which justifies the issuing of a new plan number, but effectively these plans are first cousins to each other. They have the same network, and the same plan type (EPO) which means the same gatekeeping requirement and the same lack of an out of network benefit. There are minor differences in cost-sharing for expected utilization for a healthy individual. But these plans are very similar to each other. They are all priced within a 3.5% band of each other.

Bright is unlikely spending significant resources to design plans for optimal plan choice and risk segmentation. Or at least that is not the only likely motivation.

Instead, I think that there is an attempt to spam buyers attention spans. The first seven plans are from Bright. Most of the first page of results are from Bright. Since buying insurance is not an inherently pleasant task, the extra options hack attention and could plausibly discourage individuals from further searching as the next result is more of the same, and the result after that is more of the same.

I’m only picking on Bright as I was looking at Denver for something else last night. This is not an uncommon strategy to both dominate the benchmark premium and increase the search costs for buyers who are overwhelmingly likely to buy just on price and want the shopping experience to be done with as quickly as possible. It is likely a profitable strategy for Bright and other spammers but it is quite plausible that is leads to choice errors on the part of buyers.

J.

Navigating plans on Healthcare.gov is a nightmare. We are moving to Florida and needed to buy new insurance. There is only one provider in our part of Florida, Blue Cross Blue Shield (FloridaBlue), but there were at least a dozen plans in each category and I spent hours determining which plan was best, taking in worst case scenarios or TCO. My husband even reached out to an independent agent for help. And even she was overwhelmed. There has got to be a better system for picking a health plan.

Kent

I’m sure this is true. But how big of a consequence are these “choice errors”. If the health care marketplace is properly regulated then these “choice errors” should be pretty minor or even trivial. Perhaps you are paying a couple extra dollars per month in premiums relative to the most “optimal” plan. Or perhaps you have a slightly higher deductible or co-pay for a particular procedure. Or maybe your “favorite” doctor isn’t in the plan but plenty of other good doctors are. But in the grand scheme of things these are all pretty trivial “choice errors” that really aren’t life changing in any way. Sort of like picking a less reliable Chevy Malibu over a more reliable or efficient Honda Civic. Both will get the job done even though Consumer Reports tells you that the Honda is the better choice. You don’t really need to make the most optimum choice, only an adequate one.

On the other hand, in a poorly regulated marketplace then truly egregious plans like those “faith-based” healthcare cooperatives that aren’t actual insurance would be foisted on unsuspecting people. And making the wrong decision could have egregious consequences.

David Anderson

My research has found that a particular type of choice error is equal to 2 to 3 weeks of pre-tax pay just in terms of excess premium.

quakerinabasement

It’s like laundry detergent or breakfast cereal. Two or three major competitors flood the market with so many offerings they dominate shelf space.