I have a new early draft working paper in conjunction with Alex Hoagland (University of Toronto) and Ed Zhu (Boston University). This will be presented for the first time at the APPAM conference in two weeks and we need a lot of feedback as we know we are not as tight as it needs to be.

Our question — How do people act in the liminal time from receiving a medical service and actually receiving the bill?

This matters a lot. An increasing number of people get their health insurance through plans that have substantial deductibles. This means people pay a lot out of pocket for their early care. However once they hit their deductible their spot price of future services either goes to co-pay or coinsurance amounts which are much lower than full contracted price or they go to nothing. At that point, the high deductible health plan model predicts people will use a lot more marginal services. The entire HDHP paradigm assumes people are good shoppers for healthcare. Brot-Goldberg et al demonstrate that high deductibles are good at reducing total utilization but people suck at shopping for high value care.

We’re poking at a question within this realm.

We hypothesize that there is a temporal information and belief mismatch.

Most people when they go to the doctor’s office or a hospital for a shoppable service don’t know precisely what they will owe on their deductible until the claim is processed. They have to form a belief about how much they will owe. This belief could be right. It could be wrong. It informs future spending decisions for the patient and their family. It creates a fuzzy knowledge period between getting a service and getting the bill from their insurer. The fuzziness becomes clear once the bill actually arrives.

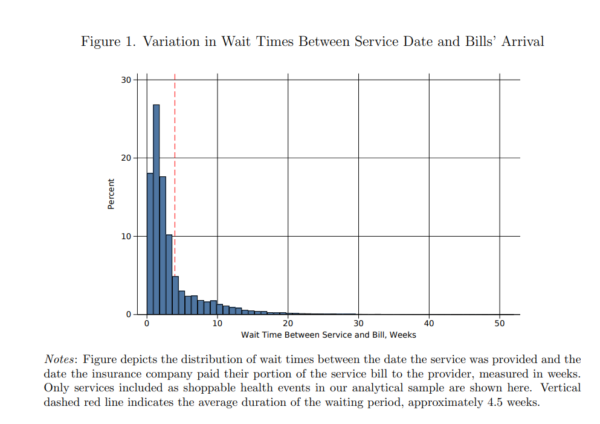

We leverage the fact that insurers don’t receive nor pay claims instantly. Instead there is wild variation between insurers, between providers and over the course of a year on the gap between when a service is performed and when a claim is paid. We don’t see the bill’s arrival, we just see the first date when an insurer could send an accurate bill to a patient and their family.

I discussed this in 2017 during repeal and replace when there was a nerdy discussion about individual risk rated premiums with individualized risk rated premiums:

claims and diagnoses don’t come in instantly. Individual providers/hospitals/physician groups do not have a universal timeline to file claims. My kids’ pediatrician files claims within two days and gets paid within ten days of the service. My PCP files claims on the 1st and 15th of the month. My wife has one provider who files weekly. The other provider has a claim from several months ago that has yet to hit payables.

We look at two periods of spending of the rest of the family after a shoppable event. The first portion is the spending after the service but before the bill. The second portion is after the bill arrives. We have three conditions on how people think about what could be in the bill:

- Just about right so we would expect spending to be about equal between these two periods

- Underestimate the real costs so we would expect more spending in the post bill arrival period relative to the post-service/pre-bill period. They will initially act as if their spot prices are higher than they are but the bill tells them that they have met their deductible and their spot prices crash for future services.

- Overestimate the real costs. In this case more people think they have met their deductible and use more services in the pre-bill arrival period and perhaps cut back in the post-bill arrival period.

Given that health insurance is messy and confusing, I felt a priori that people would get it right would be unlikely. However that is our null hypothesis that there is nothing happening here.

I did not have a strong prior on the other two options. Give me two beers and I’ll argue for an underestimate. Give me three beers and I’ll argue an overestimate is more plausible. (BTW, I would like to replace confidence intervals with a beers scale… my co-authors keep on shooting me down).

So what did we find?

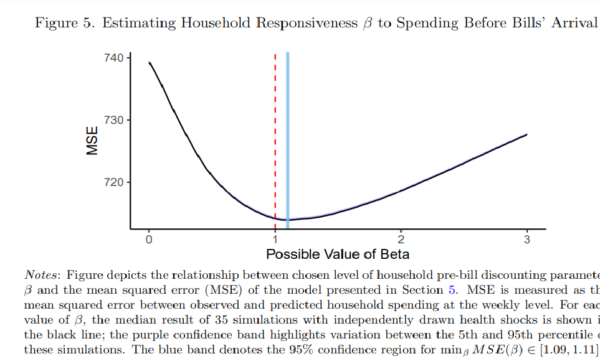

The beta coefficient is our estimate of the patients’ estimate of their expected bill compared to the actual bill. We find that people modestly over-estimate their cost-sharing in the liminal period. We then find that people who have not spent a whole lot and are pretty far from their deductible do the worst.

Now why does this matter besides it being cool math combined with insurance geekery?

We expect patients to act as rational consumers. We have excellent evidence that people don’t “get” deductibles in the way that we expect people to conceptualize deductibles and value of care. We think that our findings provides a partial explanation as to what is happening here. There is a quasi-random information gap where people are guessing at what they actually owe and acting on that likely to be wrong information.

We estimate that a fairly decent number of people are exposed to this problem. We also estimate that this exposed cohort spends significant sums that they likely would not have spent. Changing the information that people see could plausibly save, for US healthcare expenditure purposes, a small but real number that in any other context is pretty big (We could probably buy at least the NFC South and perhaps parts of the AFC North with the money at stake). This is a solvable problem. We have this information problem solved at the pharmacy where almost everything is adjudicated in almost real time.

So for the health economists who read Balloon-Juice. What are we doing wrong? What should we add for robustness? What makes you think we’re full of shit? What should we do better?

Tony G

The medical billing system is dysfunctional in so many ways. A couple of weeks ago I got a bill for some bloodwork that had been done in April. “All of the charges were rejected by insurance”, so now I’m battling with the lab and my insurance company about things that happened more than half a year ago. I wonder whether any intrepid economists have calculated the total person-hours that are wasted on this nonsense every year by patients, medical offices, hospitals and insurance companies?

A Man for All Seaonings (formerly Geeno)

I remember once not getting a bill for an ER visit for more than a year after the event. Because insurance changes every year (even if you get the same plan it’s a new policy) the insurance rejected all the billing since my current policy didn’t cover me for the period in question.

I got resolved eventually, but our system sucks.

To answer your question, I don’t really concern myself about the timing of their billing, since they don’t seem terribly concerned about the timing of their billing.

Ohio Mom

@Tony G: I’ve often wondered something similar, phased thusly: If we spend 1/3 of our lives sleeping, what perecent do we spend on arguing with health insurers? Those arguments can be years apart but very time and effort intensive when they do occur.

Now so far in my life, given the combination of being covered and having some financial security (in the form of steady enough income and modest savings), I have not worried about deductibles, co-pays, indecipherable EOBs, and the like.

I certainly do not understand the drug payments under my Part D plan. Oh sure, I know they is a doughnut hole but I am not going to make a spread sheet and a graph of what I spent on each med during what period and would it be possible to game the system by buying the more expensive ones first or does the commutative law apply?

I do gulp when the periodontist demands payment in advance but all I can do is take out the checkbook. Again, because I am middle-class enough to afford it. It wasn’t pleasant shelling out for a new heat pump either but no choice on that either.

In short, I think overwhelmed-induced apathy describes me best.

Argiope

Just here to second the beers scale. Things would be much more fun.

Lymie

Interesting. Quick thoughts:

In figure 1 – the median time would be a better measure than the mean.

I think that you need to do a stratified analysis – look by HH income, price/cost sensitivity is not universal. You probably don’t have HH income, but you might have zipcode in your data and could link on census info about median HH income (we found both median zip income and personal income to be associated with outcomes separately).

Also, age – if you have Medicare, is the behavior different? Finally, what would you uncover if you look by gender or race?

I think that you might be missing a more complex story.

David Anderson

@Lymie: We don’t have any geography or household characteristics beyond the age/gender and coverage characteristics…

I agree with you I would expect heterogeneity of response. Our data is middle to upper income heavy but we don’t have household specific details.

Another Scott

If anyone really believes that, they have not interacted with the US healthcare system in any substantial way.

I have BCBS via my giant employer. About 30% of the time, the medical office bills the wrong BCBS office, then I get a letter saying that the claim was denied in some jargonese saying it was denied because I have “different coverage” (when my coverage hasn’t changed in 30+ years). The last time it happened, I called the office and explained that whatever issue it was wasn’t my fault and they needed to file the claim correctly.

My J has to file claims herself because her physical therapist doesn’t take insurance. So she gets to deal with them claiming that the wrong code was used (when the code hasn’t changed in years), she needs to refile, etc., etc.

The US medical system is designed to put up roadblocks to paying money out. There are seemingly no incentives for efficient delivery to patients. (Insert rant about waiting in doctor’s offices after showing up early for an appointment – patient’s time has no value!!) Look at the incentives and follow the money.

Thanks for continuing to push the boulder up the hill. I admire your tenacity.

Cheers,

Scott.

Lobo

For what it is worth. People are very conservative on the front end. Probably not a good thing, avoiding medical treatment they need. But once on the other side, they use more than probably what they really need. The incentives encourage that. We want health care to be used on a more uniform level.

Lyrebird

I have no clue. I am not a great shopper for health care, I know from personal experience that lower cost is often not as good care, and I AM SO DISCOURAGED FROM DEALING WITH THE INSURERES’ SHENANIGANS TO DENY CLAIMS that I just give up.

Was going to switch from our PPO to an HMO plan to try and send a message, but I realized it would only save about $200 or less over a year, and it would mean having to give new card numbers to all my kids’ doctors and specialists. Ugh.

Tony G

@Ohio Mom: Yeah, it’s a tremendous drag (literally and figuratively) on our economy and culture. Of course, I’m lucky to have any medical insurance coverage at all — tens of millions of Americans still have no coverage and suffer and die unnecessarily as a result. But even for lucky people like me it’s a tremendous waste of time and a big source of aggravation. It’s a major burden on the medical “providers” also. Every doctor’s office pays one or more people to do nothing but fight insurance companies all day, and hospitals have entire departments that do nothing but that. I worked in I.T. at a major New York City hospital (Sloan-Kettering) and the biggest user of computing resources was the Patient Accounts department — the department that battles with insurers for reimbursement. Great system!

randy khan

That’s an interesting topic. I imagine things have improved significantly in this area since 1996, but when my dad died I was fascinated and confused by how variable medical billing was. It certainly wouldn’t have facilitated making rational choices about his medical care.

I received bills over a period from about a week after he died to well over a year later (at which point his estate had been closed for at least six months).* Some of this, I think, was because my father didn’t sign up for Medicare Part B and doctors first tried to get paid that way, failed, and then billed him, but I never have figured out what was going on with the bill that came 18 months after he died.** The doctor who was most useful to us as a family, who was dad’s primary care physician, didn’t bill us at all, although I think that was intentional.

*I sent a polite but firm note back to the doctor saying the estate was closed so there was nobody to pay.

**It was weird that he hadn’t signed up for Medicare Part B, but he worked in an ER before he retired, so I kind of wondered if he was getting some kind of professional courtesy from his doctors.

Tony G

@Lyrebird: The whole concept of “shopping for health care” is a right-wing fantasy that is both idiotic and cruel. With rare exceptions of “truly elective” procedures, that is not the way that human health and medical care works. Twenty-six years ago I needed emergency brain surgery that effectively saved my life. I had no idea that I needed the surgery until an emergency required it — and once I was in agony due to the emergency I was in no shape to get out of bed, let alone “shop around”. Any right-wing politician who talks about “shopping around” for medical should be beaten with a baseball bat (see “Casino”) and then denied treatment — but perhaps I’m not being civil.

Central Planning

We have a HDHP. With 5 kids and some maintenance drugs (frovatriptan is stupid expensive), we are always into the co-insurance and I think for the past 8-10 years, we have gotten beyond that every year to the point where healthcare is “free” (i.e. no payments/co-insurance).

My wife can not wrap her head around the economics of the plan. Sometimes she will skip a month of medicine because she has enough and thinks that will somehow save us money in the long term (knowing we will max out the plan anyway). I’ve tried to explain that if we spend (to make the math easy) $24k on healthcare every year, it doesn’t matter if we spend $8k/month for 3 months or $2k/month for 12 months.

So, we are not good shoppers for healthcare. We know what the worst-case cost for a year of healthcare will be and we try to maximize that spend earlier than later so we have more time to get the “free” healthcare.

Speaking of billing, my daughter is currently fighting with our big in-network medical organization. They referred her to another doctor, and she made the appointments and contact that doctor through the original providers Epic system. Turns out that doctor is out of network, but use the tools of the in-network doctors.

Also, our gastroenterologist group will not be part of the UHC network starting next year. They couldn’t come to an “agreement” which probably means UHC doesn’t want to pay their rates. They are one of the few independent specialists around here. :/

Ken

From my (thankfully) limited experience with health care, the biggest billing uncertainty is that period after you get the hospital bill, but before you get the statement from the insurance company saying how much of that you have to pay.

Barbara

So in my experience, one thing that might be in play for purposes of whether people have the ability to find a lower cost provider is provider market power to reduce the availability of information (or in some cases alternative providers) to the consumer. That’s what I would like to know. How does competition between providers in a given zip code or region affect price shopping?

Background:

Whenever I consider HDHPs, I scratch my head and wonder what’s really driving the model, aside from the obvious, which is a pretty substantial payment penalty on people with chronic illness. Anyhoo. One thing I have considered is that the push to be “cost conscious” at the margins is really part of an effort to drive people to use lower cost providers generally. Because, as everyone knows, referral patterns are sticky. If you select a lower cost provider (drug, laboratory, whatever) for one interaction, you will likely stick with it for future interactions.

Providers know this as well as insurers, and so they resist to the nines actually having to provide information to consumers, and I can tell you that the resistance is even greater to the idea that an insurer could incentivize referrals to lower cost providers, such as, for instance, by encouraging use of non-hospital ambulatory services (like, say, MRI, ASC, etc.) instead of hospital outpatient facilities that charge insurers more and usually try to tack on a whopping facility fee. The success of a provider in resisting these measures is typically tied to market power in one or more lines that the insurer “must have” in order to meet network adequacy and/or competitive network requirements.

Another Scott

Now that I got that rant out of my system, returning to your post:

Perhaps I’m not understanding the issue well enough here.

Understanding that you’re trying to think about the behavior of large groups and what that means for public policy, I don’t think that people work that way. Patients are not “rational consumers”. When I visit a doc and get a statement, it usually says what my BCBS deductible is and what my estimated share to be paid is. Even if/when people don’t get a statement like that, I think that very few people like going to the doctor, and only go when they have to (unless it’s a 6 month checkup or something nominal like that). Taking time off of work, taking the kids out of school, etc., etc., is a hassle. It’s expensive in many ways. People go because they have to. It costs what it costs – they aren’t “shopping” for a deal.

People who can afford it pay the bill and sigh and get on with their lives.

People who can’t afford it, pay what they can and fight with the billing department for months/years on end. They still buy food and gas and other things that they need to keep on living. Too many people, still, have almost no ready cash at the end of the month, so a medical bill just gets added to the pile to chip away at some day…

I’m not sure that there’s a way to tease out the effects you’re hoping to find from the (as you point out) wide variation in billing practices. I’m not optimistic that, say, a federal mandate that medical bills are provided at time of service, list deductibles and patient share in clear language, are void (or taxed at $100) if not final-billed within 30 days (like the way the ports were cleared of shipping containers by threatening a $100 per container fee if they’re not picked up) would help, because of all the routine errors in billing. Maybe if there’s a way to restrict the study to controlled well-matched groups – dunno. I think it might be very hard to get actual data from real people:

“What did you spend when last year on your medical care? Think back to last April when you crossed your deductible – did you go out to dinner more in May??” :-/

The solution to this problem (of “too much healthcare usage”) isn’t to have an early-year hard dollar limit where insurance kicks in. That creates these pathologies that you’re trying to solve via more information to patients. (Most) People don’t like going to the doctor. Those that do (for conversation, attention, whatever) can be addressed in other ways (counseling, etc.). If you want to have a deductible, spread it out (instead of $1000/year, make it $100/month or something). People don’t have fewer medical issues in the first quarter than the 4th…

My $0.02.

Thanks again.

Cheers,

Scott.

Barbara

@Central Planning:

This is another obvious issue. How is consumer price sensitivity affected by the likelihood that it doesn’t really matter because they are likely to meet the deductible no matter how “prudent” they are with individual services? I guess you would try to look at utilization across years if you have it. Because if you are going to spend $7500 this year no matter what, the burden of price shopping might seem excessive. There are some drugs that are so expensive you will leapfrog across the deductible in just a few months.

Kelly

Back in 1997 when the first Mrs. Kelly’s breast cancer metalized she had emergency brain surgery then a lot of other stuff. We had excellent health insurance from my IT job at Intel. However several months later we started getting notices from the hospital that $170,000 would be sent to a collection agency unless we paid up. I called them. “Oh, the charges are being negotiated. This happens all the time and our system automatically sends those out. No one can fix it. Ignore them.” I told them I’d been IT support for accounting systems for a couple decades and it damn well can be fixed. Have them call me and I’ll come in and help them sort it out. They never called. The bills eventually went away.

way2blue

David, I can’t speak directly to your question, but for me, with ‘decent’ health insurance (FEP BC/BS), generally my medical app’ts are annual check-ups.

This year I finally had foot surgery ($$$) that I’d been postponing for years. And the pre-op app’t caught a few health issues that needed further testing. Plus I had a knee injury that required medical attention and now physical therapy. And an issue with one eye… So I pushed to have everything addressed this year to run up to the maximum out-of-pocket threshold—which I reached—rather than string medical costs over a couple years. Thus all remaining medical bills are no charge. I have inadvertently paid some co-pays after the threshold was reached, so now I need to make sure those are reimbursed…

FWIW. There is a significant time lag (weeks to months) between the medical app’t and the EOB. Sometimes the bill arrives before the EOB, but I always wait—to be sure they match.

gene108

I’ve been told repeatedly, when I was responsible for shopping my employer’s health insurance plan, that insurers will reduce rate hikes with higher co-pays (back in the early 00’s, before high deductibles caught on) and higher deductibles (later on) because people will less likely seek care lowering the claims they have to pay upfront or if their are claims the insurer pays less upfront.

The consumer cost structure of an insurance plan – deductibles, co-insurance, etc. – over the last 20 years, seems more about discouraging utilization to save insures from paying claims.

I remember back when Bush, Jr. rolled out high deductible plans and HSA’s and knew immediately Republicans talking about consumers being savvy shoppers and the power of the free market will fix healthcare was bullshit. I’d helped too many employees deal with claims that I knew no one has a clue what a service will cost upfront.

Probably a much heavier lift, David, but knowing how much something costs is probably as important as when the bill gets received or comes due.

It sounds simpler than it probably is to implement, but some fixed pricing, or narrow range of prices, for services would do wonders for everyone involved in healthcare from providers to insurers to consumers.

Barbara

@gene108:

I don’t actually accept this premise because insurers know how hard it is to actually shop for value — barriers to transparency abound, for one thing, even assuming you are willing to shop and/or second guess your provider. Now, you should do that for certain types of services, like clinical labs — yes, go to the one that your insurer prefers and for heaven’s sake never go out of network. There is zero benefit for doing that.

Also, that savings you get when you are in the deductible are just measly from the insurer’s perspective — the real expenses of health care utilization are in categories that jump over the deductible amount in a single episode of care, if not a single day’s worth of encounters.

The heart of the HDHP model is just a transfer of the cost of medical care to sick people. It’s a softer way of imposing a preexisting condition limitation — softer, except in the sense that you have to incur the penalty every year.

So maybe that’s why, among all the other impediments, you don’t actually see “intelligent” value based shopping.

Eunicecycle

@Tony G: That’s what my SIL does for the Cleveland Clinic. He says the VA is the worst to deal with.

Bill Hicks

Thank you David for trying to make a completely fucked-up system less fucked-up. I despair about our “health” care system. I avoid it like the plague as my experiences have mostly been hugely stressful with no benefits to my health completely due to the insurance based funding system. As a college biology prof, I often wonder to myself why any of these students want to get involved in such a horrific system when they could do just about anything. I also have lost faith in physicians considering they were instrumental in getting this system firmly in place and don’t seem to want to end it (https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/patient-support-advocacy/ama-vision-health-care-reform). I guess my rant is to wish that folks like you and physicians would spend a lot more time on pointing out that insurance based systems are fundamentally stupid (useless middlemen just add to costs) and less time trying to fix stupid.

Barbara

@randy khan: I remember when, probably within the last decade, Medicare began requiring providers to submit claims no later than 12 months after the date of service. There was a lot of handwringing. People cite Medicare’s “efficiency” wrt administrative costs, but they don’t really understand the low costs often reflect a lot of slack in other ways.

But it’s not just Medicare. I had an acquaintance whose only child died of cancer and she was still getting various bills from a local children’s hospital more than three years after he died. I felt anguish on her behalf. I can only imagine what she felt

ETA: If you are wondering what the limit was previously, it depended, but it was something like by the end of the second year — E.g., if DOS was 4/1/21 you would have until 12/31/22 to submit the bill.

randy khan

@Barbara: That’s interesting, and a little scary. I will say that the last bill was more amusing than annoying, since we knew we didn’t have to pay it (and had never seen the doctor – it was someone who’d been in the ER when my dad was taken there, IIRC).

PaulB

“We expect patients to act as rational consumers.”

Well, now, there’s your problem….

In all seriousness, as others have noted above, it’s bloody difficult to act as a “rational consumer” in the health care market, mostly because so much of the information we need is (mostly deliberately) hidden from us.

A story, just because I feel the need to rant: I maxed out my deductible and total out-of-pocket expenses for the year earlier this year due to hernia surgery in March. A few months later, I had a rotator cuff injury that required physical therapy. I was properly referred by my examining physician, the treatment was approved by the insurance company, and I selected a physical therapist from the preferred provider list. The total cost to me should have been zero.

The insurance company processed the various claims filed by the therapist for the 3-month treatment (a separate claim filed for each week of treatment) and notified me that I would have to make up a $1,500 shortfall. Even worse, the claims were handled inconsistently, with multiple outcomes for identical treatment and claim codes filed by the therapist, with payments as low as $6.50 (not a typo) and as high as $350.00 to the therapist for identical claims.

That was two months ago and I have not seen a follow-up bill from the therapist. As a rational consumer, I should probably have followed up with them immediately. As a regular human being who absolutely does not want to deal with this shit, I’m putting my head firmly in the sand and hoping that the therapist will point out the inconsistencies to the insurance company and that they will reach a mutually agreeable resolution that will not involve me, and that I will, when all is said and done, owe nothing.

So, which should I plan for? Owing nothing, as I hope (and, in my opinion, should expect)? Or that I owe $1,500, as the claim notifications from the insurance company suggest? This rational consumer has absolutely no clue. (Fortunately, I am able to absorb the cost if needed, painful though that will be to my budget in the short term.)

StringOnAStick

The system is full of perverse incentives. I got my first knee replacement, realized we’d hit our deductible so rather than wait until the next calendar year, I had the second replaced 15 weeks later as a BOGO free. I used a famous ski doctor clinic and it was expensive, and I notice that this clinic is no longer on the list for that employee insurance plan, probably because of me. Oh well, I just had a fine morning skiing powder so the knees are working out nicely.

Or the friend who had crap insurance for years so touched the medical system as little as possible because his plan (through the job he retired from) paid for very, very little. Now that he’s on Medicare, he’s getting years of issues taken care of, things that were really reducing his quality of life.

The system is chaotic and designed to drag out payment for as little as possible for as long as possible. Europeans and Canadians think our system is cruel and insane; I can’t disagree with them.

Chris T.

I’m a great health care shopper. When the hospital has a special on kidney surgery, that’s when I go for my kidney surgery! If the kidney stones come before or after the special, why, they just have to wait!

(Likewise, a decade ago, I waited until a year after I died from cancer to have my cancer treatment when it was on sale.)

Lymie

@David Anderson: Well, that’s unfortunate. But certainly look by age and gender, then. I am more familiar with using claims data, or finding proxies for income, because that is the elephant in any health related analysis.