"'Buckley' is very clearly the result of slow thinking and methodical research, which makes it precisely the sort of work that its subject could never produce." defector.com/william-f-bu…

— Defector (@defector.com) July 18, 2025 at 3:59 PM

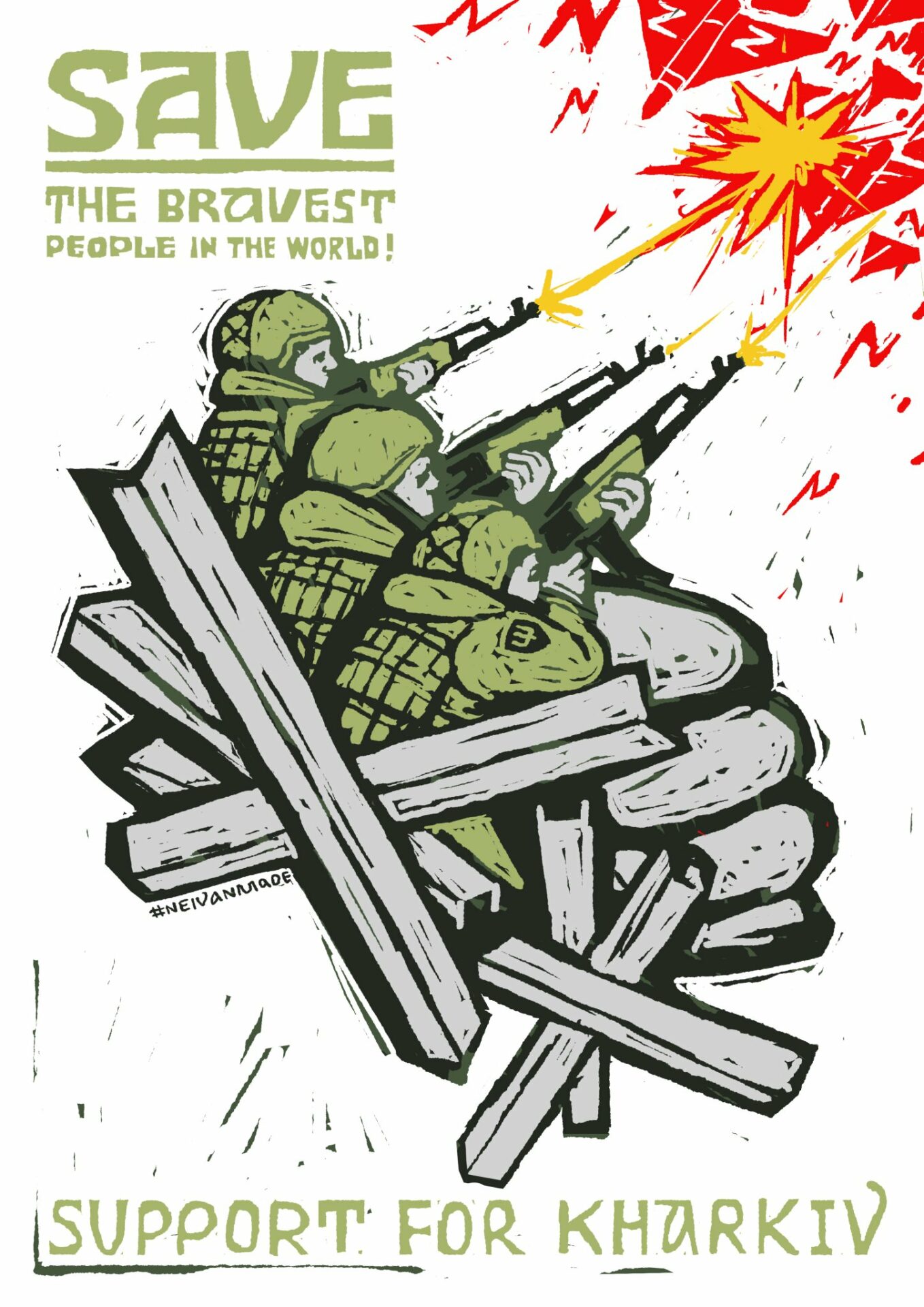

Even if (like me!) you’re not a sports fan, Defector is absolutely worth price of a subscription. Political fads tend to age like a dead fish in the summer sun, and the National Review is a publication whose inception was as ludicrous as its current much-mocked state. Here’s Brandy Jensen with a book review:

Perhaps the highest praise I can offer a book that took 27 years to complete and runs over 1,000 pages is that I can see why, and that it doesn’t feel like it. Sam Tanenhaus’s extremely long and anxiously awaited biography of the man who founded National Review, and is often regarded as the architect of modern American conservatism, arrived with a resounding thud on my doorstep. There is no way that a book the size of Buckley: The Life and The Revolution that Changed America could arrive quietly. It is, in many ways, a remarkable accomplishment: exhaustive but not tiring, serious yet lively, both affectionate and suspicious. It is almost dizzyingly populated with recognizable characters—the result of Buckley’s famed and enormous social influence—which offers regular satisfaction both to readers who like knowing what Sylvia Plath thought of the Buckley family home, and ones who yearn to learn more about cranky Viennese ex-Leninists. Most of all, Buckley is very clearly the result of slow thinking and methodical research, which makes it precisely the sort of work that its subject could never produce.

William F. Buckley Jr. went for quantity instead. He wrote dozens of books, including non-fiction and a bestselling series of spy novels, both of which were mainly dashed off while on skiing vacations in Gstaad. He also produced three columns a week for decades, generated prodigious written correspondence, and appeared in 1,504 episodes of Firing Line, all while editing the magazine and accepting regular speaking gigs. For years, Buckley promised to write a serious work of political theory—he managed to produce thousands of words railing against his liberal enemies, but was ultimately thwarted by his inability to offer a coherent elaboration of what conservatives were really about…

For that deep thinking, Buckley relied on his frequent collaborator and brother-in-law, Brent Bozell, along with mentors like Whittaker Chambers (the subject of Tanenhaus’s previous, much-lauded work of biography) and protégés-turned-apostates like Garry Wills. These were the men with the ideas; Buckley provided the packaging, and a singular talent for holding together groups with potential disparate motivations under the banner of a revived conservative movement. Or, anyway, this is the received wisdom: Buckley the gatekeeper, yoking these headstrong types together in common cause while expelling more distasteful elements like the Birchers, in service to lacquering the American right-wing with a sheen of respectability. It is a strong brand, but it has some visible wear and age on it by now.

Buckley’s legacy has been somewhat troubled since Tanenhaus first began work on this book, years before the first episode of The Apprentice would air; reading it today, it’s tough to avoid the sense that Tanenhaus was caught in a bit of a bind. The man who gave us Reagan, as Buckley is often known, is a thorny enough historical consequence; Tanenhaus largely leaves alone the question of whether he paved the way for something worse. Reagan is elected president on page 824, and the remainder of Buckley’s life and legacy gets fewer than 50 pages. For all the minute attention paid to how Buckley did it, we are still left wondering what exactly he did.

Excellent Read: <em>‘William F. Buckley’s Bill Never Came Due’</em>Post + Comments (83)