Blogger’s note: The annual Science Online conference/unconference is going live this Thursday in scenic Research Triangle, NC. I’ve been going since the second meeting, way back in 2008 (I think…), and this year I will be moderating a couple of sessions. One of them is called “The Uses of the Past,” jointly led (or unled) by Eric Michael Johnson, who studies at the University of British Columbia while writing the excellent Primate Diaries blog at ScientificAmerican.com. What follows is the email exchange within which we discussed first thoughts about history, writing and research in anticipation of this session. Which is another way of saying: this is kind of off the main track of this blog — so keep on going if you want another one of those back-of-the-book bits I sometimes post, and pass by in silence if you prefer your snark undiluted.

_______________________________________________________________

I’ve always found that the best way to tackle a complicated story – in science or anything else, for that matter – is to think historically. But even if I’m right in seeing a historical approach as an essential tool for writers, that’s not obviously true, however well (or not) it may work for me. Science news is or ought to be new; science itself, some argue, is devoted to the task of relentlessly replacing older, less complete, sometimes simply wrong results with present-tense, more comprehensive, and right (or right-er) findings.

Thinking about this, I put together a panel on the Uses of the Past that was held at last year’s World Conference of Science Journalists in Doha, Qatar. The panelists – Deborah Blum, Jo Marchant, Reto Schneider and Holly Tucker led a discussion that was lively and very supportive of the history-is-useful position (not to mention valuable in itself). But the conversation was far from complete.

So we’re going to do it again, this time at Science Online 2012. (You can follow all the fun by tracking what will be in a few days a tsunami on Twitter, tagged as #scio12). This is an “unconference,” which means that I and my co-moderator, Eric Michael Johnson will each present what amounts to a prompt – really a goad – for the audience/participants to run away with. As Eric and I have discussed this session, one thing has stood out: where I’ve thought of the term “uses of the past” as a challenge to writers about science for the public, an opening into approaches that will make their work better, Eric has been thinking about the importance of historical thinking to the practice of science itself – what working scientists could gain from deeper engagement not just with the anecdotes of history, but with a historian’s habits of mind. So just to get everyone’s juices flowing, Eric and I thought we’d try to exchange some views. Think of this as a bloggy approach to that old form, the epistolary novel, in which we try to think about the ways in which engagement with the past may matter across fields right on the leading edge of the here and now.

So: if, dear reader, you’re intrigued thus far, read on.

_______________________________________________________________

Dear Eric,

I have to confess; I’ve never needed convincing about history; I’m a historian’s son, and all my writing, just about, has had a grounding in the search for where ideas and events come from.

But all the same, it’s simply a fact that the professional scientific literature from which so many stories for the public derive seems, on first glance, to be as present-tense as it is possible to be. As I write this, I’m looking at the table of contents of <a href=”http://www.sciencemag.org/content/335/6064.toc”>my latest (January 6) digital issue of <em>Science</em></a>. In the “Reports” section – where current findings are deployed — there is nothing but the now and the near future under discussion. Just to pull up a few of pieces at whim: we can learn of the fabrication of wires on the nano-scale that obey Ohm’s law (an accomplishment its makers claim will support advances in both classical and quantum computing to come). We can read of a new measurement of the ratio of isotopes of tungsten (performed by some of my MIT colleagues in concert with researchers at the University of Colorado) that suggests (at least as a preliminary conclusion) that the terranes that make up the earth’s continents have remained resistant to destruction over most of the earth’s history. And then there is a report from researchers into that living genetics/evolution textbook, <em>C. elegans</em>, that adds yet one more telling detail within a broader understanding of the intertwined behavior of genetic and environmental processes.

All of these – and all the rest of what you can find in this issue of that journal, and so many others – tell you today’s news. Each of these could form the subject of a perfectly fine popular story. Yet none of these do or necessarily would as popular stories engage the history that lies behind the results.

That is: you could tell a story of a small step taken towards the goal of building a useful quantum computer without diving into either the nineteenth century’s investigation into the properties of electrical phenomena or the twentieth century’s discovery of the critical role of scale on the nature of physical law. You can talk about the stability of continents without recognizing the significance of that research in the context of the discovery of the intensely dynamic behavior of the earth’s surface. You certainly may write about mutation rates and stress without diving into that old fracas, the nature-nurture argument that goes back to Darwin’s day and before. This is just as true for the researcher as the writer, of course. Either may choose to ignore the past without impairing their ability to perform the immediate task at hand: the next measurement, the next story.

You could, that is, but, at least In My Humble Opinion, you shouldn’t. From the point of view of this science writer, history of science isn’t a luxury or an easy source of ledes; rather, it is essential for both the making of a better (competent) science writer, and in the production of science writing that communicates the fullest, most useful, and most persuasive account of our subject to the broad audiences we seek to engage.

In briefest form, I argue (and teach my students) that diving into the history of the science one cover trains the writer’s nose, her or his ability to discern when a result actually implies a story (two quite different things). It refines a crucial writer’s tool, the reporter’s bullshit detector. At the same time, explicitly embedding historical understanding in the finished text of even the most present-and-future focused story is, I think, more or less invaluable if one’s goal is not simply to inform, but to enlist one’s readers in gerunds of science: doing it, thinking in the forms of scientific inquiry, gaining a sense of the emotional pleasures of the trade. I’ll talk more about both of these claims when my turn comes around…but at this point, I think I should stop and let you get a word in edgewise. Here’s a question for you: while I can see the uses of the past for writers seeking to extract from science stories that compel a public audience – do working scientists need to care that much about their own archives. What does someone pounding on <em>C. elegans</em> stress responses, say really need to know about the antecedents of that work?

Best,

Tom

_______________________________________________________________

Dear Tom,

The British novelist, and friend of Aldous Huxley, L.P. Hartley began his 1953 novel <em>The Go-Between</em> with a line that, I suspect, many working scientists can relate to, “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” The process of science, much like the process of art, is to dredge through what has been achieved in the past in order to generate something altogether new. That is perhaps the only thing that the two fields of creative endeavor have in common; the past must be understood only so that you can be released from it. However, much like you, I’ve never needed convincing about history either. While I agree that the past can be a foreign country at times, I’ve always enjoyed traveling.

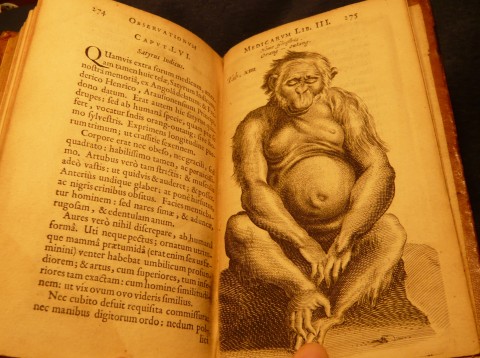

I came to history through my work in science, but I found that understanding the historical context for why scientists in the past came to the conclusions they did helped inform the questions I was asking. I’ve always believed that the scientific method was the best way of eliminating our own personal biases when seeking answers about the natural world, but that unexamined assumptions can still slip through the scientific filter. By examining how these flawed assumptions made it through I hoped it would help me in my own work. Perhaps the best way to explain what I mean by this is to briefly discuss how an early brush with history encouraged me into the research direction I ultimately pursued in graduate school. The book was <em><a href=”http://www.amazon.com/Natures-Body-Londa-Schiebinger/dp/080708901X”>Nature’s Body</a></em> by the Stanford historian of science Londa Schiebinger that I found in a used bookstore during my senior year as an undergraduate in anthropology and biology. In one chapter of her book she discussed the early history of primate research and how the prevailing assumptions about gender influenced the hypotheses and, as a result, the conclusions about those species most similar to ourselves. One of the earliest descriptions of great apes in the West, after <a href=”http://www.timeshighereducation.co.uk/story.asp?storycode=415874″>Andrew Battell’s exaggerated stories about “ape monsters,”</a> was by the Dutch physician Nicolaes Tulp, probably the most widely recognized figure in the history of science that almost no one has ever heard of.

In 1632 Tulp commissioned the artist Rembrandt to paint his anatomy lesson, which ended up being one of the Dutch master’s most famous works (if anyone today recognizes Tulp’s name, it’s most likely from the title of this painting). Nearly a decade after he posed for this portrait Tulp published his Observationes Medicae (Medical Observations) in which he described the anatomy of a female ape he’d received on a ship bound from Angola. He was immediately struck by the similarities with humans and the drawing he published, identified as Homo sylvestris, demonstrated a striking example of cultural bias. Made to look the way he assumed this female would appear while alive, Tulp emphasized his own culture’s gender stereotypes. The female sat with her hands in her lap, framing what appeared to be a pregnant belly, and her head was glancing downwards in a distinctly demure pose.

By itself this depiction wouldn’t have been particularly revealing; it was just one individual allowing their own social biases to influence his science. What was remarkable, however, is the way Schiebinger showed how Tulp’s depiction would appear time and time again in the subsequent centuries when describing female primates, not just in appearance but also in behavior. More than two hundred years later, when Darwin described the differences between males and females in his theory of sexual selection, he had the same unmistakable gender bias that influenced his thinking. I had never taken a women’s studies course in my life, but this insight was an enormous wake up call for me. I realized there had been a common set of assumptions that endured for centuries, what the historian Arthur Lovejoy called “the spirit of the age,” and had gone unexamined until relatively recently when a new generation of primatologists–such as Jane Goodall, Sarah Blaffer Hrdy, and Frans de Waal–began studying the female half of the equation that had been largely ignored as an important area of study. Knowing this history pushed me to ask different questions and focus on a topic that I discovered hadn’t been addressed before: why female bonobos had such high levels of cooperation despite the fact that they had a low coefficient of genetic relatedness (violating the central premise of <a href=”http://scienceblogs.com/primatediaries/2010/05/punishing_cheaters.php”>Hamilton’s theory of kin selection</a>). Different scientific topics have their own entrenched assumptions that otherwise critical researchers may not have considered; that is, until they see the broad patterns that a historical analysis can reveal.

Cheers,

Eric

_______________________________________________________________

Dear Eric,

I love your story, partly because the original painting is so extraordinary and it’s good to have any excuse to revisit it. But I value it more for your argument that engaging with the thought and thinking (not quite the same thing) of scientists past fosters insight into present problems. That goes just as much for science writers – that is to say, those seeking to communicate to a broad public both knowledge derived from science and the approaches, the habits of thought that generate those results.

Rembrandt’s painting itself gives some hints along this line. There’s a marvelous and strange discussion of the work in another novel written in English, W. G. Sebald’s <em><a href=”http://www.amazon.com/Rings-Saturn-W-G-Sebald/dp/0811214133/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1326733737&sr=1-1″>The Rings of Saturn</a></em>. There, Sebald points to the fact that none of the anatomists are actually looking at the corpse under the knife. Tulp himself stares out into the middle distance, whilst other members of his guild peer instead at an anatomical atlas open at the foot of the table. As Sebald studies the one of the often-discussed details of the painting, he argues that what appears to be simply an error in the depiction of the <a href=”http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17225789″>dissection of the left</a> hand reveals an artist seeking to see past the formal abstraction of the lesson, drawing attention instead to the actual body on the table, the physical reality of a single dead man.

Not wishing to push too hard on that (unproven, unprovable) interpretation, Sebald still points out something that rewards the attention of science writers. Rembrandt depicts both facts — the body, the tendons of the exposed hand – and ideas, at a crucial moment of change in the way natural philosophers sought verifiable knowledge.

We see, amidst the reverence for the book, the authority of prior learning, an event actually occurring on the canvas: the effort to extract understanding from the direct testimony of nature. Amidst all else that can be read there, Rembrandt’s painting reminds the viewer of the time – not really all that long ago – when a fundamental idea was being framed with its first answer: yes, it is possible to understand biological forms as machines, and to investigate their workings directly.

So, to take the long road home to the question of why bother with history when covering the news of today and tomorrow, here are two thoughts (of the three with which I will hope to provoke our fellow unconferees on Thursday). First: as you argue for scientists, understanding of the past can lead writers to stories they may not have known were there.

To give an example, I’ll have to leave anatomy behind (about whose history I sadly know very little). I recently had an occasionto look back at <a href=”http://books.google.com/books?id=KniUvcxFtOwC&pg=PA281&lpg=PA281&dq=michelson+sixth+decimal+place+ryerson+physical+laboratory&source=bl&ots=0oDZa8vpy3&sig=6_BQaDfvsUE-G_nLWBmNF8l4boM&hl=en&sa=X&ei=91oUT_3mAeXq0gHvuI22Aw&ved=0CE8Q6AEwBg#v=onepage&q=michelson%20sixth%20decimal%20place%20ryerson%20physical%20laboratory&f=false”>A. A. Michelson’s infamous remark</a> from 1894 when he asserted that physics was done except for that which could be discovered in the sixth decimal places of measurements.

There is a lot wrong in that claim, but if you look more closely at what he said, you can find something less obvious in Michelson’s claim – and that can lead to insight into what goes into the making of all kinds of very modern physics, from (possibly true) observations of faster than light neutrinos to the ways in which cosmologists are extracting knowledge from high-precision measurements of the cosmic microwave background (and much else besides, of course).

So there’s a story-engine chugging away inside history, which is there to be harnessed by any writer – facts, material, from which to craft story. There’s also a story-telling tool, a method that derives directly from historical understanding. A core task for science writing is the transformation of technically complicated material into a narrative available to broad audiences – which must be done without doing violence to the underlying ideas. If the writer remembers that every modern problem has a long past, then she or he can prospect through that history when the problems and results in that sequence are intelligible to any audience. For just one last, very quick example: general relativity is a hard concept to explain, but framing the issue that it helped to resolve in the context of what Newton’s (seemingly) simpler account of gravity couldn’t handle – that spooky action at a distance that permits the gravitational attraction of the sun to shape the earth’s orbit – and you’re in with a chance.

Best,

Tom

_______________________________________________________________

Dear Tom,

I think you touched on something very important with regard to the idea that science writing is a transformation that takes the technical language of science (primarily mathematics and statistics–that is, if it’s done correctly) and interprets it into the communication of everyday experience. Science writing is a process of translation. The history of science as a discipline is precisely the same thing, though historians typically engage in a different level of linguistic analysis by looking at language meaning and the way that science provides insight into the process of historical change. But it seems that there is no better way to think about how the history of science can be useful to science journalists than to consider what we do as essentially a process of translation. Art is involved in any translation work and there is never a one-to-one correspondence between the original and what it eventually becomes. We must be true to our source material but also evoke the same overall meaning. To put this more simply: why are the findings being reported important to scientists in a given field and how can that same importance be conveyed to a readership with a very different set of experiences? It seems to me that there are two primary ways of doing this: engaging with the history of <em>why</em> this question matters or tapping into contemporary <em>attitudes</em> that evoke connections with the findings reported (where the latter approach <a href=”http://scienceblogs.com/primatediaries/2009/10/grand_evolutionary_dramas_abou.php”>goes wrong</a> happens to be one of my <a href=”http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/primate-diaries/2011/09/02/male-chauvinist-chimps/”>favorite</a> topics of critique, one that is <a href=”http://www.huffingtonpost.com/eric-michael-johnson/intelligent-design-creati_b_636200.html”>unfortunately</a> an extremely rich resource to draw from).

However, there is one other reason why the history of science is important for science journalists that we haven’t quite touched on yet. A journalist who knows their history is better protected from false claims and the distraction of denialism. The scientific press release is a unique cultural invention and all too often seeks to manipulate journalists into framing a given story so as to exaggerate that study’s actual impact. The historically minded journalist is less likely to get bamboozled. In a similar way, the <em>he said-she said</em> model of reporting is a persistent and irritating rash for almost every professional journalist I’ve interacted with. But the temptation to scratch is always present, even though the false equivalency reported is rarely satisfying over the long term. The history of science can be the journalistic topical ointment. Those who know the background of anti-vaccine paranoia, or who recognize the wedge strategy of creationist rhetoric, can satisfy their need to report on a story that captures the public’s attention while also providing useful information to place that issue within it’s proper context. History matters.

Your friend,

Eric

—

Eric Michael Johnson

Department of History

University of British Columbia

http://www.history.ubc.ca/people/eric-michael-johnson

http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/primate-diaries/

Images: Johannes Vermeer, Lady Writing a Letter, betw. 1665 and 1666.

Hans Holbein the Younger, The Ambassadors, 1533.

Nicholaes Tulp, “Homo sylvestris” Observationes Medicae, Book III, 56th Observation, 1641

Rembrandt van Rijn, The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Nicolaes Tulp, 1632

Samara Morgan

Edge engages with science history in this years Edge question.

Tuesday, Jan 17, 2012

2012 : WHAT IS YOUR FAVORITE DEEP, ELEGANT, OR BEAUTIFUL EXPLANATION?

rlrr

“Who needs science when you have the Bible?”

— The GOP

jeffreyw

@Samara Morgan: 42

RossInDetroit

I’ve seen that Holbein painting in person but I have no memory of visiting the National Gallery when I was in London. The anamorphic skull is truly strange.

Gonna read the rest of this over lunch, but the great painting caught my eye.

Benjamin Franklin

Interesting discussion, Tom.

The past as prologue is a two-edged sword. Yes, we must use stepping stones

already set by our predecessors, but without being too dependent on the nerve pathway most travelled.

I am a big believer in heuristics, or as some call it, ‘brain-storming’ past our

predilections and considering the impossible, as possible.

Villago Delenda Est

“History is bunk” — attributed to a disgusted student in one of “Professor” Newt Gingrich’s history classes when told by the professor that Jesus Christ was a venture capitalist who cornered the market on myrrh on the Jerusalem Commodities Exchange.

Villago Delenda Est

Oh, come on. The purpose of “journalists” in THIS country is to sell newspapers/garner ratings. Knowing history is a distraction from those all important cocktail weenies and fluffing the powerful for access. There is no time to process information that distracts from the primary mission: making a shitload of money for the corporate parasites who control the whole shebang.

Linnaeus

Speaking as a historian of science, I greatly appreciated this piece.

gaz

@jeffreyw: FTW!

jibeaux

More importantly, Research Triangle is not in any sense of the word scenic, but there are some decent restaurants and bars, and a decent art museum. Where you going after the conference? Where do the geeks congregate, Chochki’s or Flinger’s?

DZ

@ Samara Morgan:

Cosmic happenstance

PurpleGirl

Words to live by:

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Never make anything simple and efficient when it can be complex and wonderful.

burnspbesq

If you’re in the Triangle, a trip to Bullock’s in Durham is highly recommended. One of the great barbecue joints anywhere.

Wag

Reading this, I am again struck by the disconnect between reporting and stenographing, as outlined by last week’s NYT debate. The ability to put stories into historical perspective is key to putting a story in context, and to allow our understanding of facts to evolve as information comes to light. Lamark aand Darwin both put forth views of evolution, and if stenographers had their way, we would have graduate students trying to figure out how much upward force is required for a giraffe’s neck to grow. FSM knows how many giraffe heads would have been pulled off in the process. Instead, erroneous theroies have been discarded, and Darwin’s theories have won out.

For now.

The stenographers may yet win if we cannot push back against ID.

cmorenc

I live in Raleigh, NC and have truly been asleep at the switch, because this thread is the first I’ve heard about this conference. Unfortunately, registration is already full so it appears I’ll have to miss out on your sessions in person Tom, except perhaps to follow it online.

RossInDetroit

@PurpleGirl:

@PurpleGirl:

I realize you’re not being serious but I spend a great deal of time trying to replace complex things with simple ones. I’d rather have a simple thing that can be understood and repaired than a complex thing doing the same job that has to be discarded and replaced when it fails. Complexity is wonderful until you need a microscope to fix it. Those of us with screwdriver calluses really like simple.

Fucen Pneumatic Fuck Wrench Tarmal

for what little its worth, i always considered the absence of any historical context in science and technology writing to be a conscious choice to weed out those who hadn’t been keeping up with the required homework.

that is, if you haven’t followed the progress of real science, computing, even consumer electronic gadgetry, since you acquired the core concepts, or if the core concepts are lacking, they want to keep their newest and latest amongst themselves.

of course that is me taking it too personally that i don’t know everything going on, and i find it too difficult to read real science literature. but i think even beyond that, if you want to evangelize your field, you have to give people exposure to the shiniest new objects, and some ability to detect bullshit on their own, to really engage people not already heavy into it.

cmorenc

@burnspbesq:

Or, Clyde Cooper’s in downtown Raleigh (but they are strictly a daytime restaurant and close at 6pm, and so may not work so well). The truly greatest barbecue joints in North Carolina are an hour away in Wilson, NC, Parker’s and Bill’s. The “combination plate” ordered with “white chicken” is to die for, and includes generous portions of barbecued pork, fried chicken breast, brunswick stew, hot paprika boiled potatoes (much more delicious than it sounds), and cornbread sticks…be sure to order sweet iced tea with it. Parker’s is such an old-fashioned traditional place that they still do not accept credit cards, but OTOH the place has quite literally not changed in over 50 years. The same table and chairs (and wall paneling) are still there from when I ate there as a 5yo with my grandparents, and I’m 62yo now. I’d swear the waiters are even the same, except that’s obviously not true, but they do all have a natural unstudied retro-look to them as if it could literally be so.

gaz

@RossInDetroit: I kind of sit the fence on this.

I believe true genius is coupled with simplicity. – the simpler some great thing is, the more amazing it is for it’s simple solution.

I also like to be able to repair things.

That said, I think there’s something to be said for the notion that making something “repairable” and “simple” has it’s cons:

1. Sometimes “simple” just won’t do what we need.

2. Things that are repairable often cost more to build.

3. Efficiency – Consider modern circuts and micro-components. Yeah – you can’t solder the board. But the board uses less power, and less raw material goes into it’s creation.

Just playing a little devil’s advocate is all.

gaz

Hi Tom!

You realize that your divider image – http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/primate-diaries/files/2011/07/Page-Break-Image.jpg.jpg

Is WAAAY too wide right?

it needs to be shortened by at least a 3rd. – almost 1/2

You’ve destroyed the BJ layout. Since it’s not your image, but rather SA’s, I humbly suggest you remove it from your post entirely.

Tom Levenson

@gaz: Fixt (I think).

SiubhanDuinne

@RossInDetroit: And I know I’ve seen the Vermeer in person, but I would have sworn it was at the Frick, not the National Gallery.

Paul in KY

@jibeaux: The best thing about it is that it is approx 150 miles from the beach!

gaz

@Tom Levenson: Works now!

One of the many hazards of content aggregation =) heh.

Thanks!

Dr. Morpheus

Really? I see a fat ape sleeping in a sitting position. Me thinks your politically correct stereotype ‘white male must project cultural dominance in all art’ is showing more than anything else.

BO_Bill

Got to love college teachers who argue with a straight face that those who Believe in The Creation are backwards (‘hicks’). And then argue with a straight face that evolution in humans magically stopped 30,000 years ago (‘a sophisticated understanding’). I don’t know, perhaps they believe this.

But most college teachers know for sure that those people who Believe that a sub-species of humans necessarily changed when they transitioned from the Tropical Environment to a Climate of Seasons are bad thinkers (‘racists’).

College teachers are funny in this manner.

Amir Khalid

@BodyOdor_Bill:

Who, exactly, is arguing that human evolution stopped 30,000 years ago? Can you cite any scientist in the relevant field making this improbable claim?

Sly

Broad agreement. History provides context, and allows you to tackle arguments and counterarguments in ways that are unavailable to you without it.

But there is such a thing as bad history; when its used improperly to bolster a claim. Presentism is likely my chief pet peeve in this regard: when someone drags a historical figure or event out of their contemporary context to give an argument what they believe is added weight or to make themselves seem intelligent and, by extension, their claims more thought out. In reality it is pathetically lazy and adds nothing of worth to the discourse.

And even if you can’t quite put your finger on it, you know it when you see it. It’s the reason why most here disdain David Brooks. He sure can wax poetically about the nationalist fervor of Alexander Hamilton, but what Brooks tries to do is use the writings of men who have been dead for 200 years to try and shed light on modern dilemmas. Who cares what Alexander Hamilton would think about a national health insurance mandate? Hamilton doesn’t have to deal with the intricacies of such a law because he’s fucking dead.

And not to put two fine a point on the matter, but this article is the worst abomination ever printed in the New York Times.

Sly

@BO_Bill:

If you know a biology teacher, at the college level or otherwise, who insists that humans have not been subjected to selection pressures with respect to reproduction for 30,000 years, then you should immediately contact their supervisor and let them know that they have someone on their staff who is woefully unqualified.

Or you could just be full of shit.

gaz

Water is wet. BO_Bill makes shit up.

The last time he ever cracked a book was when he was give the Hardcover copy of “Debbie Does the Dishes”

The troll is ABSOLUTELY CLUELESS.

I doubt he could find his home state on a map.

BO_Bill

Steven Jay Gould, MIT.

gaz

@BO_Bill:

From the final damned paragraph.

I expect your eyes glazed over after grappling with all of the polysyllabic phrases in the piece, and so you just gave up.

Yutsano

@Sly:

With BoB, door number two is always a safe option.

gaz

@Yutsano: The only option.

Tom Levenson

@BO_Bill: Not to mentn that Gould was a Harvard professor, not a member of the MIT faculty. So while I was proud to win money off of SJG, (betting the A’s over the Red Sox in that late ’80s playoff series), and greatly admire much of Gould’s writing, I take B.O.B’s error here as a measure of both the motives and worth of his posting.

BO_Bill

Last time I checked the Truth has its own motive. Fine, my apologies to MIT. It was Harvard.

gaz

@Tom Levenson: LOL. I didn’t even bother to check. The problem with engaging with Bullshit Trebuchets like B.O.B. is that you have to spend so much time countering 30 pieces of bullshit on one end of the post, that a couple of other areas of bullshit from the other end of the post go unfielded. it’s simply overwhelming. Like being the only guy left on the hockey team that’s still in the rink – and trying to play goalie.

Do you think overwhelming people with bullshit is a debate tactic, or do you think it’s simply rank stupidity? or is it both?

I’m just curious. =)

mclaren

@PurpleGirl:

More words to live by: any sufficiently advanced theoretical physics theory is indistinguishable from gibberish. C.f. string ‘theory’ so-called.

The big story of modern science is the way it’s moved backwards into a new dark ages. String ‘theory’ (so-called) makes no actual testable physical predictions, despite 40-plus years of frantic effort. String ‘theory’ belongs to the same category of intellectual artefacts as David Ickes”theory’ that all the world’s royal families descend from extraterrestrial reptilian aliens.

But it’s not just theoretical physics that has moved backwards into a new dark ages. Here’s Paul Krugman speaking about contemporary economics:

Source: “A Dark Age of Macroecnomics (Wonkish),” Paul Krugman, 27 January 2009, The New York Times.

In fact, everywhere we look, valid knowledge is being destroyed and replaced with superstition and drivel and long-debunked fairytales. We’re moving backward as a civilization into the Great Endarkenment, the reverse of the Great Enlightenment of the 18th century. Americans are building Creation Museums at a furious rate: individual American states (this week it’s Missouri; next week, who knows? Mississippi? Alabama?) are now scrambling to pass laws requiring schools to tech vacuous “creationist” twaddle in the classroom as though it were real science.

Charles P. Pierce summed it up pretty well in his 2005 article in Esquire magazine, “Greetings From Idiot America.” If anything, it’s gotten worse since then. I’m just waiting for congress to draft a new law requiring electrons on the internet to be arrested if they carry copyrighted material.

RSA

This is great stuff, Tom. I was especially struck by this:

I’ve been doing a fair amount of popular science reading lately, and I’ve realized how difficult a balancing act this is. Focus too much on the pure ideas, and the result can be too much like the dry recitals of a textbook. Focus too much on the scientists, and the ideas can be overshadowed by personalities. Giving the “true” story about how some idea arose can be too complicated to retain the readers’ interest. Of course, lots of science writers do an excellent job managing these issues, and more.

joel hanes

@BO_Bill:

I have read Gould’s The Mismeasure of Man.

Nowehere in that book does Gould claim that human evolution ceased 30 kyears ago, or on any other date.

What Gould does say is that the concept of human race, as traditionally understood, has no basis in biology.

Further, he presents evidence that all modern human populations seem to have roughly equivalent genetic endowments with respect to “intelligence” (whatever we may define intelligence to be).

Two questions for Bill :

1. How many ancestors do you have in the generation that lived 2000 years ago ? (Correct for re-crossing lines of inheritance in any way that seems good to you.)

2. What was the total human population of the world 2000 years ago ?