The New York Times has a good story from the 15th on a False Claims Act lawsuit filed by a former United Healthcare employee. It alleges UHC systemically defrauded the US government of billions from up-coding its Medicare Advantage claims to get bigger risk adjustment payments. This is a big deal. Medicare knows that the incentive in Medicare Advantage is to make the patients look as sick as possible to maximize upcoding. A recent estimate has coding differentials leading to a $20 billion dollar a year payment differential between Medicare Advantage and Fee for Service Medicare for intrinsically similar patients.

At the heart of the dispute: The government pays insurers extra to enroll people with more serious medical problems, to discourage them from cherry-picking healthy people for their Medicare Advantage plans. The higher payments are determined by a complicated risk scoring system, which has nothing to do with the treatments people get from their doctors; rather, it is all about diagnoses.

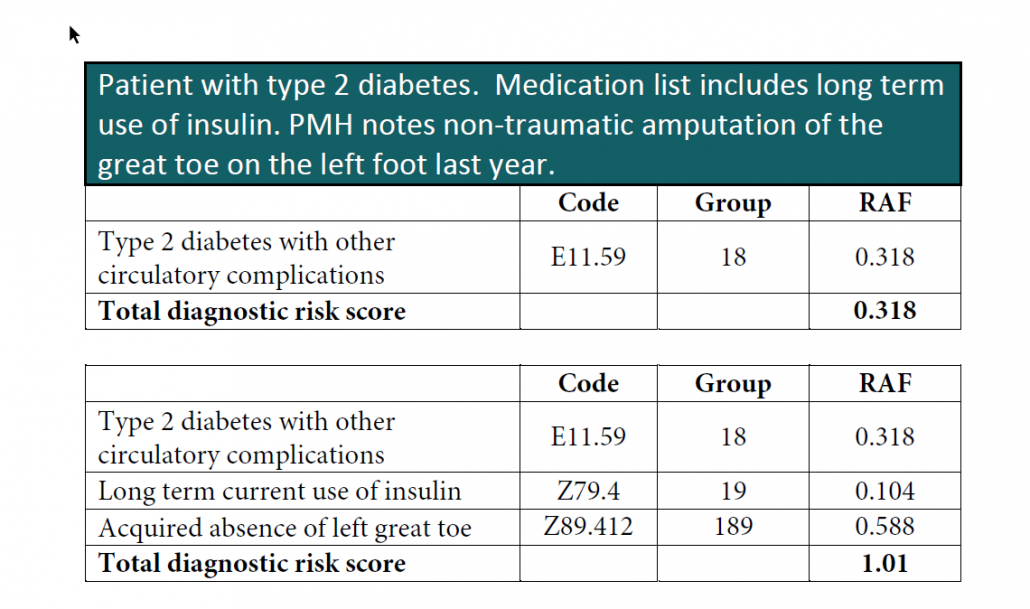

Diabetes, for example, can raise risk scores by varying amounts, depending on a patient’s complications. So UnitedHealth gave people with diabetes intensive scrutiny, to see if they had any other conditions that the diabetes might have caused.

As Mr. Poehling’s lawyer, Mary Inman, described it, the government would pay UnitedHealth $9,580 a year for enrolling a 76-year-old woman with diabetes and kidney failure, for instance, but if the company claimed that her diabetes had actually caused her kidney failure, the payment rose to $12,902 — an additional $3,322. Ms. Inman is with the law firm of Constantine Cannon in San Francisco.

We need to differentiate between aggressive coding and fraud. The key question in this example is not whether or not UHC got a doctor to say that the kidney failure was caused by diabetes but whether or not the evidence in the chart supports that assertion.

If it is medically supported from the chart, history and corroborating results, this is not fraud. It is aggressive coding designed to maximize revenue. If it is not supportable, then it is either fraud or abuse. That will be the key area of argument. Does the evidence show that the diagnosis codes that UHC is chasing are supportable by medical evidence?

Betsy Nicoletti is a coding specialist who shared her coding book with me. I want to highlight a legitimate example of what happens at every health plan that has risk adjusted plans. The example is about diabetes:

A non-risk adjusted plan won’t care what is coded. The doctor will probably just code E11.59 and go from there. It is medically supported and it is enough to get a claim paid.

The incentive is different for risk adjusted plans. Both of those coding clusters are accurate descriptions of the patient’s medical condition. One is just worth several thousand dollars more in revenue than the other. The risk adjusted plan will push its providers hard to code the triple combination of E11.59, Z79.4 and Z89.412 instead of just E11.59.

The hard push means aggressive data mining. It means contacting provider offices with lists of suggested diagnoses for patients. It means giving up widget incentives for closing diagnoses. It means running sessions by coders for coders on how to maximize risk scores. It is what I did for my last position at UPMC Health Plan.

The key question in the law suit is whether or not the diagnoses are actually medically supportable, not whether or not UHC pushed its providers to code aggressively within the limits of medical evidence.

From a wider policy perspective the incentive structure of diagnosis based risk adjustment encourages insurers and increasingly physician led Accountable Care Organizations and shared savings groups to maximize their risk score to maximize or protect their revenue. It does nothing directly to improve the health of their members with only an indirect potential benefit of matching resources to needs or improving the information picture on patients. If the concern is that the incentive creates an artificially sicker looking population then the solution is to apply a fractional multiplier to the total risk score to claw back the aggressive coding upside. If the concern is fraud, then CMS needs to fully fund and conduct comprehensive auditing.

Aggressive coding is not inherently fraudulent.

Barbara

Would love to comment but can’t. I do agree that it’s very easy to allege fraud and very difficult for everyone involved to balance the positive and negative incentives inherent in risk adjusted payment.

Neldob

Still trying to get my mind around Medicare Advantage v Fee for Service Mmedicare. Sigh. Thanks as always.

David Anderson

@Barbara: Preach — I had to rewrite this post a couple of times to get to a point where I could make my point without stepping in any holes.

Lee

Could searching for this type of fraud be automated?

I’m guessing currently they just wait for a tip and then start the manual search of records for that provider.

Barbara

@Lee: Speaking generally, fraud statutes are a very blunt instrument for trying to redress the inherent weaknesses of an agency’s policy. Systematic changes that better align the policy with the objectives and results that CMS and Congress are trying to achieve through risk adjusted payment would be a much better use of resources.

Uncle Cosmo

Just for curiosity’s sake, WTH are “widget incentives for closing diagnoses”?

Lawrence

I used to be a business analyst for the pro fee group in a hospital. I did an experiment once plotting the office visit coding as a curve. The ER physicians, individually and as a group, reliably produced a normal distribution curve. They weren’t certified as a trauma unit, so it was just whatever people walked in with. There were other specialties where the curve was actually an aggressive slope. Some providers never marked anything but a level 5 visit. These tended to be the ones who were most attentive to the workings of the RVU based bonus system we had.

Barbara

@Lawrence: If you mark everything as a 5 you are extremely vulnerable to a simple stupid challenge that 45 minutes times 25 patients during the course of a day means you had to have been at work for nearly 20 hours, yet you clocked in at 8:00 am and out at 3:00 pm and found 90 minutes to eat lunch. And if their employer the hospital rewards them, well, you know, reckless disregard and all that. Now, if they only saw 10 patients and they required intensive intervention, that’s a different story.

EL

Good summary. I also work with a medical group on this. (Note that long term use of insulin is in the diabetes without complications category, so it would not add RAF as the toe amputation would.) Some groups, mine included, are very paranoid about being accused of fraud. Others, not so much.

David Anderson

@Uncle Cosmo: You get paid a per diagnosis closed payment:

IE the data search thinks there are 100 diagnoses that could be coded for your practice. The insurer pays $50 per closed Dx over the next nine months… the value of the incentive payment is not tied to the value of the diagnosis. It is tied to whether or not a widget (the Dx code) is produced on a claim.

Barbara

@Uncle Cosmo: To provide a little more context. The risk adjustment process requires a face to face encounter between a doctor and a patient every year. Some health plans know based on last year’s data that a given person almost certainly has a diagnosis but if they aren’t seeing encounters being logged, they will not be able to use it for RA purposes. So they come up with various protocols to at least make sure that such members have encounters with doctors that are sufficient to lead to a diagnosis if one exists.

Uncle Cosmo

@David Anderson: I have no doubt you are trying to explain this in layman’s terms, but it still makes no sense to me. (E.g., what does it mean to “close a diagnosis”?)

IMO there is a minimum level of familiarity with concepts & terminology necessary to understand this rather arcane field. I don’t have it, nor am I willing to dedicate the (probably not inconsiderable) time & effort to acquire it. I should’ve stayed out of this thread, as I normally do, so now I will back out of here & leave it to you & the handful of Juicers who are health-care-policy wonks. Sorry for wasting everyone’s time & eyeballs.

Uncle Cosmo

@Barbara: That makes things slightly less opaque to me, but only slightly. Not enough to follow the discussion, much less contribute to it. Again, sorry for wasting everyone’s time.

Lawrence

@Barbara: Management was well aware of that concern. They brought the in coding analyst to make a version of the low volume high complexity excuse. I never really bought it because why should provider X have such a different patient mix than provider Y in the same specialty group. Also, because the individuals implicated were the most caustic and unmanageable in the hospital. And the more RVUs they billed, the more they got paid. I had to monitor it from time to time, but as long as we weren’t getting sued nobody really cared.

Arclite

We’re a competitor of United out here in Hawaii, and they do some really dicey things to make their plans cheaper. Luckily we have a reputation for quality and customer service, so our customers tend to stay loyal, but I would love to see them get dinged on their bad behavior.

Barbara

@Uncle Cosmo: You aren’t wasting my time (I am but that’s another story). It is assumed without further information that every Medicare beneficiary has an average risk (although certain de facto adjustments are made re gender and age). So that’s a risk score of 1. Certain diagnoses cause that score to go up, and when that score goes up, payment goes up. Let’s say, a person has a diagnosis of diabetes. A person who is diabetic typically stays that way, but a diagnosis for risk adjustment purposes must be re-established every year through a face to face encounter with a doctor. That puts pressure on plans to make sure those suspected high risk adjustment diagnosis patients get seen and get diagnosed. They try to make sure this happens by creating lists and incentivizing doctors to see those patients, and a variety of other practices. It’s whether those incentives and practices tip over into being fraud or not that is the subject of the original post.

Eric

I understand that Medicare may pay insurers more for sicker patients, but aren’t the hospitals and doctors paid the same amount regardless (unless they code a level 5 visit for every patient)? How are insurance companies incentivizing hospitals and doctors to code more? I’d assume that for most, it takes extra effort to code three ICD-10 codes for a patient rather than one. It doesn’t provide better healthcare and so I’d hope that providers actively avoid unnecessary paperwork.

David Anderson

@Eric: Yes and no. Providers are paid the same for the same code for any/all patients that they see. However they will see a patient with five chronic conditions and complex care needs far more often than they will see a patient with slightly high cholesterol. They’ll make more money from more encounters with the patient with lots of co-morbidities.

Insurers will make sure providers who code to the limit of the record get paid for it either through paying them direct incentives or arranging for shared savings scenarios. In shared savings the target for spending is risk adjusted (a patient with cancer should cost more than a patient without cancer, all else being equal), so aggressive coding ups the limit where savings are activated.

Barbara

@David Anderson: Testing the limits here, but the real problem for plans is not with the sickest patients who are always in the doctor’s office and for whom risk adjustment should not be that difficult. The problems are the patients with chronic conditions who are more likely to turn up in the ER than the doctor’s office for whatever reason. The in between problem is that there may be patients who are not being coded with the same intensity or the same number of diagnoses that they could be.

Scott

This concern with coding to the “highest level of appropriate specificity” is increasingly critical for the provider organizations themselves as more and more of their revenue is derived from “value-based” contracts that off-load risk from the payers to the providers.

Since shared savings calculations derive from efficiently managing a patients’ care not in absolute terms but relative to their risk, providers need to represent how sick their patients are as accurately as is appropriate (but not one diagnosis more). That’s a tricky line to walk but a necessary one.

I worry whether the outcome of this suit and the potential for others like it will discourage provider groups from aggressively pursuing advanced payment models. If the line between aggressive/accurate coding and fraud is unclear from a provider risk management perspective, I am concerned it won’t be possible to fairly compare performance within or across provider groups to determine who is able to most efficiently care for patients (especially if attitudes toward risk management differ across providers)