RAND’s Russian sympathizing senior political scientist, Samuel Charap, is still flogging his argument that Ukraine needs to give in to Putin’s demands for Ukraine’s own good. Because it includes a long excerpt followed by my own response and analysis, I’m going to deal with this after the jump. I will provide one teaser of my analysis/response. What we are seeing in Russia’s genocidal re-invasion of Ukraine and Ukrainians’ amazing resilience in defense of their state, society, and culture is an existential war. Putin has made it very clear that he, and through him Russia, gets to determine what Ukraine is, what its future will be, and even if their will be a Ukraine in the future. This is now not just an interstate war, it is an existential one. And the last time the US was involved in an existential war at all was World War II. The last time it was involved in an existential war that would directly determine whether the United States would continue to exist going forward was the Great Rebellion, now doing business as the Civil War.

More after the jump.

Here is President Zelenskyy’s address from earlier today. Video below, English transcript after the jump.

Smile of every child, every lesson conducted by Ukrainian teachers today is proof that Ukraine will definitely endure – address of President

1 September 2023 – 19:47

Dear Ukrainians, I wish you good health!

I just held a meeting of the Supreme Commander-in-Chief’s Staff. In fact, the entire meeting is about the situation at the front now.

The Commander-in-Chief, commanders. A separate closed report by Defense Intelligence Chief Budanov.

The situation in the East, in the South, on the left bank of Kherson region. Supply of ammunition. Missiles for our air defense. Equipment. Ukrainian production of weapons. Many different nuances, many different details. The key is to give our soldiers even more necessary for offensive operations, for demining, for the evacuation of wounded soldiers. Each meeting participant clearly understands what he should do.

There was a meeting with law enforcement officers – they continue cleansing the state of those, who are still trying to weaken Ukraine from the inside. Autumn should be fruitful in this matter – especially for Ukraine.

I took part in a very representative Italian forum – the Ambrosetti Forum. It is one of the key European platforms for policy development. Those solutions that are needed. Economic, security, political. I thanked Italy for all the support provided. But I urged never to give up our natural strength – the strength of the entire free world. Strength to act together. To the full. For our common interests. Just as we have been operating for 555 days of the full-scale war.

And most importantly for today. The most emotional. I’m sure not just for me.

More than 3,700,000 Ukrainian children started the new school year today. Most of them are in Ukraine. Most of them are offline or in a mixed mode, where social interaction between children is still preserved.

Of course, we will do everything to make it possible for them to return to schools and universities across all our land – as usual. Without online. The shelter creation program will be implemented. And we will return freedom to our entire land. The smile of every child today, every flower that children brought to school, every lesson that Ukrainian teachers conducted today, and every dream that arose today in Ukrainian children are all proofs that Ukraine will definitely endure. Life goes on. Life is getting stronger. And there will be a day when September 1 will be equally peaceful and safe throughout our land. Glory to all who bring this time closer! The time of our victory.

And today, I would like to personally thank everyone who has already taken an interest in our new educational project, the public project – the Mriia application, which I presented and which will soon be able to become part of the life of every child who is studying and who strives for his result together with all of us. Together with Ukraine.

Glory to Ukraine!

Let’s tuck into the Charap nonsense. This time he has laundered his Ukraine needs to give in to Russian demands for its own good meshugas to and through The New Yorker‘s Keith Gessen. Gessen provides Charap’s back story:

Charap, who grew up in Manhattan, became interested in Russian literature in high school, and then became interested in Russian foreign policy in college, at Amherst. He got a Ph.D. in political science at Oxford and spent time researching his dissertation in both Moscow and Kyiv. In 2009, he started working at the Center for American Progress, a liberal think tank in D.C. Russia had just fought a short, nasty war with Georgia, but the incoming Obama Administration was hoping to “reset” relations and find common ground. Charap supported this effort and wrote papers trying to think through a progressive foreign policy for the U.S. in the post-Soviet region. But tensions with Russia continued to increase. In the wake of Russia’s annexation of Crimea and incursion into eastern Ukraine, in 2014, Charap wrote a book, with the Harvard political scientist Timothy Colton, called “Everyone Loses,” about the background to the war. In it, Charap and Colton argue that the U.S., Europe, and Russia had combined to produce a “negative sum” outcome in Ukraine. Russia was the aggressor, to be sure, but by asking that Ukraine choose either Russia or the West, the U.S. and Europe had helped stoke the flames of conflict. In the end, everyone lost.

I first met Charap in the summer of 2017, not long after the book came out, and in the midst of a maelstrom of anger at Russia for its interference in the 2016 U.S. Presidential election. Robert Mueller had been appointed as special counsel for the Justice Department, Donald Trump had labelled the investigation a hoax, and Congress was in the process of passing a bipartisan sanctions bill against Russia. Charap was as angry as anyone else about the interference, but he thought the sanctions proposed in the bill were a mistake. “The idea of sticks in international relations is not just for beating other countries,” he told me at the time. “It’s for achieving a better outcome.” He used the example of the long-standing Iran sanctions, which had finally compelled Iran to come to the negotiating table and vastly limit its nuclear program. The sanctions on Russia, he went on, were not like that. “Sanctions are only effective at changing another country’s behavior if they can be rolled back,” he said. “And, because of the measures in this current bill, it’s going to be nearly impossible for any President to relieve them.”

In the following years, as Russia became more and more of a neuralgic subject in American politics, Charap continued to travel to Russia, engage with Russian counterparts, and look for ways to lower the temperature of the relationship. Going to Valdai—the annual conference where Vladimir Putin pretends to be a wise tsar interested in discoursing with professors on international politics—had become somewhat controversial. But, before the war began, Charap went to the conference whenever he could, and several times even asked Putin a question. “It’s my job to understand these people, and I was given firsthand access to them,” he said. “How can you understand a country if you don’t go and talk to the people involved in the decision-making?”

Nonetheless, for Charap, there was more that the U.S. might have tried to prevent the fighting. In recent months, as the fighting has gone on and on, he has become the most active voice in the U.S. foreign-policy community calling for some form of negotiation to end or freeze the conflict. In response, he has been called a Kremlin mouthpiece, a Russian “shill,” and a traitor. Critics say he has not changed his opinions in fifteen years despite changing circumstances. But he has continued writing and arguing. “This is a five-alarm fire,” he said. “Am I supposed to walk past the house? Because, as bad as it’s been, it could get much, much worse.”

At some point, this counter-offensive will end. The question will then become whether either of the sides is ready for negotiations. Russia has been saying for months that it wants negotiations, but it is not clear that it is ready to make any concessions. Most significantly, Russia has not backed off its demand for recognition of the territories it “fake-annexed” in September, 2022, in the words of Olga Oliker, of the International Crisis Group. Ukraine has said that it needs to continue fighting so it can expel the occupying forces and make sure that Russia never threatens Ukraine again.

The argument in the U.S. has split into two profoundly opposed camps. On the one side are people—not very many, at least publicly—like Charap, who argue that there might be a way to end the war sooner rather than later by freezing the conflict in place, and working to secure and rebuild the large part of Ukraine that is not under Russian occupation. On the other side are those who believe that this is no solution and the war must be fought until Putin is soundly defeated and humiliated. As the defense intellectual Eliot A. Cohen put it, in May, in The Atlantic:

Ukraine must not only achieve battlefield success in its upcoming counteroffensives; it must secure more than orderly Russian withdrawals following cease-fire negotiations. To be brutal about it, we need to see masses of Russians fleeing, deserting, shooting their officers, taken captive, or dead. The Russian defeat must be an unmistakably big, bloody shambles.

The arguments seem to be based, ultimately, on three kinds of disagreement. One is about the timing and meaning of negotiations. In a Foreign Policy piece last fall, Charap’s rand colleagues Raphael Cohen (Eliot’s son, as it happens) and Gian Gentile argued that any push by the U.S. for negotiations would send “a series of signals, none of them good.” As Raphael Cohen put it to me recently: “You’re basically telling the Russians, ‘Just wait us out.’ You’re sending a message to the Ukrainians and to the rest of our allies: the United States will put up a good fight for a little while, but in the end will walk away. And you’re telling the American public that we’re not really committed to seeing this through to the end.” Cohen added that he would feel differently if the Ukrainians no longer wanted to fight or, better yet, the Russians admitted defeat: “The bad guys have a choice in this, too. You have to get the Russians to a place where they view that they can’t win. Then we have something to talk about.”

Charap thinks this is a misunderstanding of what negotiations are and what they signal. “Diplomacy is not the opposite of coercion,” he said. “It’s a tool for achieving the same objectives as you would using coercive means. Many negotiations to end wars have taken place at the same time as the war’s most fierce fighting.” He pointed to the Korean armistice of 1953; neither side acknowledged the other’s claims, but they agreed to stop fighting to negotiate a peace deal. That peace deal never came, but, seventy years later, they are still not fighting. That armistice required more than five hundred negotiation sessions. In other words, it would be better to start talking.

Another disagreement centers on the possibility of a decisive Ukrainian battlefield victory. Charap believes that neither side has the resources to knock the other out of the fight entirely. Other analysts have also voiced this opinion, most notably General Mark Milley, the Chairman of the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff, who in a controversial comment last November compared the situation with the stalemate that prevailed toward the end of the First World War and suggested that it may be time to seek a negotiated solution. But the other side of this debate has been more vocal. They see a highly motivated Ukrainian Army, supported by a highly motivated populace. They point to the relative cheapness, to the U.S., of a war that pins down one of its major adversaries. And they believe that, given enough time, and enough Western weapons and training, Ukraine could take back a fair amount, if not all, of its territory; sever the land bridge to Crimea; and get close enough to Crimea to deter any future Russian military operations.

The final disagreement concerns Putin’s intentions. The “fight to the end” camp believes that, if Putin is not decisively defeated, he will continue attacking Ukraine. And some believe that if not stopped in Ukraine, as he was not stopped in Chechnya, Georgia, or Syria, he will keep going—to Moldova, the Baltics, Poland. They believe that European security is at stake.

Charap, of course, disagrees. He believes that it is possible to make a ceasefire “sticky”—by including inducements and punishments, mostly through sanctions, and by monitoring the situation closely. As for the view that Putin is bent, Hitler-like, on unceasing expansion, Charap is cautiously skeptical: “We have to admit that this is a more unpredictable actor than we thought. So while I’m not prepared to accept the Hitler narrative about how far his ambitions extend beyond Ukraine, I don’t think that we can rule it out.” But ambition is one thing; capability is another. Even if Putin wanted to keep going, Charap said, “he doesn’t have the means to do it—as this war has amply shown.”

To Charap, “The strategic defeat of Russia has already taken place.” It took place in the first months of the war, when Russian aggression and Ukrainian resistance helped galvanize a united European response. “Their international reputation, their international economic position, these ties with Europe that had been constructed over decades—literally, physically constructed—were rendered useless overnight,” Charap said. The failure to take Kyiv was the decisive blow. “Their regional clout, the flight of talent—the strategic consequences have been huge, by any measure.” And, from a U.S. perspective, Charap argues, any gains during the past sixteen months have been marginal. “A weakened Russia is good,” he said. “But a totally isolated, rogue Russia, a North Korea Russia—not so much.” A year ago, Russia was not deliberately targeting civilian infrastructure; now it regularly bombs Ukraine’s energy grid and port facilities. With every day, the chances of an accident or an incident that brings nato directly into the conflict increase. Charap is asking just how much that risk is worth.

“It’s not necessarily that I think Ukraine needs to make concessions,” he said. “It’s that I don’t see the alternative to that eventually happening.”

Earlier this year, Charap presented his position on the war at a security conference in the Estonian capital of Tallinn. During a hostile question-and-answer session, Edward Lucas, a former Economist editor, accused Charap of “Westsplaining,” and James Sherr, of the famed international think tank Chatham House, asked how he could be so sure Ukraine wouldn’t win the war outright. But the toughest question came from the Ukrainian activist Olena Halushka. “You are speaking a lot about the cost of fighting, the line of fighting here and there,” she said, in a strong but clear accent. “But what is your analytical perspective on the cost of occupation? Because if you take a look at what is happening, at all of the de-occupied territories, the patterns there are very similar. There are big mass graves, torture chambers, filtration camps, mass deportations—including the deportations of kids.” When Halushka concluded her remarks and sat down, the audience applauded.

Charap answered the other questions he’d been asked, but avoided responding directly to this one. When prodded by Halushka and the moderator, he said, “I don’t know exactly how to answer that question, except to say that of course I recognize there are horrible war crimes being committed under areas under Russian occupation. And it’s ultimately for the Ukrainian government to decide which is worse—the casualties that could occur as a result of the continued fighting,” or the brutality of the continued Russian occupation of Ukrainian land. Charap seemed uncharacteristically flustered. “I mean, I don’t know quite more what more to say to answer the question,” he said again.

It was the question—the tragic question—of how to think of the people who would be left behind if the line of contact were to freeze somewhere close to its current position. If the fighting went on, Ukrainian soldiers would die; if the fighting ceased, Ukrainian citizens would be trapped under a vicious and despotic regime.

I recently spoke with the Kyiv-based journalist Leonid Shvets, whom I have found, over the years, to have a knack for pithily formulating the views of the Ukrainian mainstream. He told me that conversations in which Americans came up with scenarios for Ukraine to surrender drove him up a wall. “Why don’t you surrender to the Chinese?” he said. “Give them Florida. You have lots of states, what’s one state less?” Florida, of course, was a complicated example. “Or, if you’re so eager to make a deal with the Russians, why don’t you give them some of your land? Give them Alaska.” He thought that anything short of total defeat for Putin would just mean that the war would start up again. “We went through this already in 2014,” he said.

“Here’s the problem,” he continued. “If we freeze the situation where it now is, not along Ukraine’s internationally recognized border but along whatever line the front happens to be at, then we acknowledge that internationally recognized borders are just a kind of fiction, which you can ignore. That’s a very bad lesson. And, second, if we put the borders in this new place, then we’re in a situation where this new border is worth even less than the internationally recognized border. Maybe a new military operation will move it even further, move it over here, or move it over there. So at that point it is just totally without meaning.”

Shvets acknowledged that people in Ukraine were exhausted after a year and a half of war. “No question, every day the war goes on is, for us, specific people who are lost, and specific houses that are destroyed. Absolutely. But we are not yet ready for defeat.” He went on: “There may come a point where we need to negotiate. But from where we are right now, that point is not visible to me.”

For Charap, the Ukrainian position on when to stop fighting is decisive, but it’s an evasion of responsibility to pretend that the U.S. can’t have an opinion on the matter. “You have to do this with the Ukrainians,” he said. “You can’t do it to the Ukrainians. But to suggest that we have no ability to influence them in any way is disingenuous. Like, we feel it’s O.K. to advise them about everything under the sun, but not war termination?”

Charles Kupchan, a professor of international affairs at Georgetown who served on the National Security Council staff in the Clinton and Obama Administrations, goes further. “Fighting for every last inch of Ukrainian territory,” he told me, is “morally justified. It’s legally justified. But I’m not sure that it makes a lot of strategic sense from Ukraine’s perspective, or from our perspective, or from the perspective of the people in the Global South who are suffering food and energy shortages.” He said that the U.S. Administration needs to let the Ukrainian counter-offensive play out. But at the end of this year, or maybe early in 2024, it will have to talk with Zelensky about negotiations. “I wouldn’t say, ‘You do this or we’re going to turn off the spigot.’ But you sit down and you have a searching conversation about where the war is going and what’s in the best interest of Ukraine, and you see what comes out of that discussion.”

There is much, much more at the link.

Charap’s enduring viewpoint has not garnered much support from those who actually know what they’re talking about.

Some nice discussion here of the institutionalized vacuity that so often passes for Russia analysis. By weakening the Ukrainian but not the Russian side, our hand-wringing soft imperialists kill the people they claim to be interested in saving.https://t.co/Qi9jNMNM3K

— Timothy Snyder (@TimothyDSnyder) August 31, 2023

"I'm surprised how many people glibly say, 'Let them have Crimea for the sake of peace'. How naive to think that would actually satisfy Russia or that Russia would honor any agreement, or that it would not disrupt shipping to damage Ukraine's economy."https://t.co/2oDfBZYSpK

— Ben Hodges (@general_ben) August 31, 2023

With a ceasefire Putin would be able to claim victory, and that means the aggressor winning as the world watches. You can call this a "new reality" if you want, but this new reality would be horrible and we cannot allow it to happen. We should choose to make the aggressor lose.

— Gabrielius Landsbergis🇱🇹 (@GLandsbergis) September 1, 2023

What’s interesting is there is a far better, more thoughtful, and more nuanced version of this argument made by Professor Stephen Kotkin. Kotkin is a historians of Russia in the 2oth and 21st century, as well as being one of the preeminent biographers Stalin. You may recall me referencing his March 2022 interview with David Remnick in The New Yorker. In this interview Kotkin is clear eyed about what Putin is doing in Ukraine, how Putin understands the world, and what Putin wishes to accomplish regionally and globally. Eleven month’s later he sat for another interview with Remnick. In it he delineates what he thinks Ukraine should do to secure the post-war peace. Part of why thi is a more thoughtful and nuanced version of the argument that Charap has been pushing since before the invasion began is that it 1) recognizes that the Ukrainians have agency, that they are one of the two primary actors in the war and 2) his focus is not on ending the war, but on securing the post-war peace. Kotkin then reiterated this in a May 2023 speech at the Gardiner Museum in Canada, which I’m excerpting from below.

So I’m going to talk to you a little bit about winning the peace. We only talk about winning the war. But winning the war is not nearly as important as winning the peace. You can win the war, and you can lose the peace. Let’s call that Afghanistan. Let’s call that Iraq. Let’s call that many other examples. So, if you’re in a war, how do you win the peace? And winning the peace is a multi-generational question.

So, if you gained some territory today, you didn’t win the peace. Somebody can come back for that territory, tomorrow or next year or the year after. So, winning the peace is much more important and much more complex. So for about 14 months now, I’ve been discussing with some of our best minds in intelligence and defence, how they define victory, and more importantly, how they plan to win the peace. I’ll just give you one example. And then I’m going to go backwards in time and a little bit sideways, and then come back out at the end with an answer, if that’s okay. If you’ll tolerate that kind of meandering.

So if Ukraine recovers all the territory that’s internationally recognized territory of Ukraine, but doesn’t get into the European Union, and doesn’t get a security guarantee, would that be winning the peace? Would that be victory of any sort? But if it didn’t regain its territory, but got into the European Union through an accelerated accession process, and got some type of security guarantee, but a lot of its land was still occupied, would that be a victory? Which one of those scenarios would be a victory? It’s pretty obvious that the Ukrainian people twice risked their lives to overthrow domestic tyrants in order to get into Europe. And so, that’s really the only definition of winning the peace that works.

So, if you want to get into Europe, let’s imagine you’re able—you’re not—but let’s imagine you’re able to retake Crimea militarily. So, then you have a predominantly, almost exclusively, Russian population now inside your borders, that can be instigated in a permanent insurgency against your country. What’s that going to do for your EU accession process? What’s that gonna do for your security guarantee? Who’s going to give you a security guarantee when you have a multimillion Russian population that doesn’t want any part of your country? And so, there are sentimental and understandable definitions of victory which relate to the atrocities that are committed—the whole war is an atrocity, right? The aggression, it’s nothing but an atrocity, and we hear about the atrocities it’s just heartbreaking. At the same time, we need to win the peace.

So, how are we gonna win the peace? Okay, so, if we agree that that might be an interesting question, now we’re going to step backwards and approach it from an angle that’s maybe unexpected, or let’s hope it’s unexpected. Let’s talk a little bit about China. We have a lot of stories about China, and they’re not true. Deng Xiaoping, who was a pretty remarkable fellow and was shorter than I am—I’ve got a big place in my heart for somebody that I can look like this to, rather than Paul Volcker, who was down the hall from me at Princeton, “Eh Paul, how’s the weather up there?” You know, that kind of nonsense. He was 6’5. I used to be 5’6.

Anyway, so Deng Xiaoping, this little guy, he’s looking over the water at Japan. And he’s saying, “You know, this place was bombed. 40 cities were firebombed with higher casualties than the two cities that were nuclear bombed. I mean, this place was a wreck. And now, they’re the second biggest economy in the world. What happened?” Right in his neighbourhood. And so he’s looking at that, and he’s saying they got a secret formula here. They manufacture stuff. And they sell it to those crazy Americans. This gigantic American consumer market, this domestic market in America, is just so insatiable. If you can make stuff that the Americans want, if it’s good enough that the Americans will buy it, you can grow rich. In other words, you can use the American middle class to create a Chinese middle class by manufacturing things that these crazy Americans will buy. Because that’s what Japan had done. And because that’s what South Korea did. And that’s what Taiwan did. Both South Korea and Taiwan are former Japanese colonies, and Japan was very involved in the post-colonial transformations in both of those places.

This brings us to Ukraine and winning the peace, and then we’ll go for questions. How does this work for Ukraine? So, it turns out that in order to win the peace, you need an armistice. You need an end to the fighting. You see, because Ukraine, they need Ukraine. Russia doesn’t need Ukraine. Russia has Russia. So, if you have a house, let’s say your house has 10 rooms. And I come into your house and I steal two of your rooms, and I wreck them, and from those two rooms, I’m wrecking the other eight rooms. You prevent me from taking the other eight rooms with your courage and ingenuity on the battlefield. But I’m still occupying two of your rooms and wrecking the rest of them. And you have more than a million, a million and a half of your children going to school in a language other than Ukrainian, in Polish and German. Another year passes, and another year passes. Are they still Ukrainian? You don’t have a budget, you don’t have an economy. You don’t have customs duty, you don’t have tax revenues. You’re dying. That whole courageous, ingenious Ukrainian army that we saw, is dead. They’re gone. They’re dead or severely wounded. You’re burning through your ammunition and you’re burning through stuff that nobody’s increasing production. We’re just giving stocks.

You want to increase production, you want to open up two new assembly lines to produce munitions when you’re a private company and they give you a two-year contract and you say, “Okay, I’ll deliver in 2025, the munitions.” Well maybe the war’s over in 2025, and you’ve just built two new assembly lines. So, you need a ten-year contract, not a two-year contract before you’re going to open up two new assembly lines. Otherwise, you get stranded assets. That’s where we are in the war. You’re not winning if someone is destroying your house, no matter how valorous, no matter how amazing your resistance has been. Because the Russians take up their own house and it has 1000 rooms. They don’t need your house but you only have one house, Ukraine.

So, armistice sooner rather than later. Regaining as much territory okay, but a DMZ, an EU accession process that’s more accelerated than the ones that the Western Balkans are going through. A security guarantee which is not going to be NATO. If you’ve been to Germany, you understand, NATO works on consensus. There’s no possibility of Ukraine in NATO. None. And discussion of that publicly can only undermine NATO unity. There’s the possibility of a South Korea outcome which would be very dissatisfying. There’s North Korea, it’s a menace. The families were separated. The destruction and the rebuilding, and everything else. And the threat continues. There’s been no peace treaty, only an armistice on the Korean peninsula. The Cold War is over except it’s not over. Yet they have a security guarantee and South Korea is one of the most successful countries in the world.

So that would be a big victory for Ukraine, if it came out looking like South Korea, with an armistice, a security guarantee. It might not be bilateral with the U.S.—it might be bilateral plus, where Poland joined and the Baltics joined and Scandinavians join, but it’s not going to be a NATO guarantee. The sooner you get to get to that the better. If Vladimir Putin signs a piece of paper, what’s that piece of paper worth? He’s gonna keep his word, commit to an armistice, and keep his word? Of course not. Never, except if he signs the paper in Beijing. Because if he signs the paper in Beijing, he can’t flip the bird to Xi Jinping. He’s on the hook. That’s his only bridge left. He’s burned every single other bridge.

So you want the Chinese to oversee the peace process, to oversee the armistice, because that’s the only way you can get Putin to keep his word. I know it sounds crazy, but the Chinese peace proposal is fake. Except it’s not fake. It’s the only solution. And so, Biden delivers his guy to accept the armistice and Xi Jinping delivers his guy to accept the armistice, and they sign in Beijing. Otherwise, this guy can pause and go for tea next year, or the year after, or five years. You take Crimea back, you’ve got this insurgency problem. And in ten years or in fifty years, Russians will come back for it. Maybe next year, they’ll come back for it. Boris Yeltsin demanded the return of Crimea to Russia. Boris Yeltsin in 1991, before the Soviet Union had even dissolved. So, the idea that Crimea, Russians are going to walk from this somehow, it’s tough for winning the peace.

In a situation of atrocities, where they’re murdering your civilians, they’re raping your women and girls, they’re kidnapping your children, they are destroying your cultural artifacts to eliminate any evidence that you actually do exist as a separate nation and a culture, this is a very hard argument to accept. That not being able to impose reparations and war crimes tribunals and regain all your territory is a winning of the peace. We’re nowhere near that yet. But we’re closer to it now than we were fourteen months ago. We’ll see if the Ukrainian offensive, if it happens—they actually don’t have any munitions right now because they spent them in Bakhmut. The ones we sent in January, the most munitions we’ve sent in the war, and they spent them over a territory that has no strategic significance. Now they’re demanding more, they’re begging for more. You take back some territory, or you don’t. Let’s say you take it back. How do you win the peace? How do you get the Russians to stop and not try to take it back again? Next year or the year after? You need to win the peace, not just win the war.

So, it’s very unsatisfactory. It’s very, in some ways, demoralizing. It’s very difficult politically, and it’s the best outcome that’s on the table right now, short of a miracle. A miracle would be Russian disintegration in the field, the Russian army just disintegrates. We’ve been hearing about that for fourteen months and there’s no evidence of it yet. It might happen, but there’s no evidence. We’ve been hearing about Putin having trouble and maybe being overthrown. There’s no evidence to that. It could happen. He would have to be overthrown, but not by an escalatory replacement, but by a capitulatory one.

The miracles we’ve been hoping for have not happened yet. They, once again, could happen. War is unpredictable, but if you’re looking soberly at the evidence, you’re looking at U.S. and China getting together to impose an armistice on each side, so that the fighting stops and Ukraine can get rebuilt, get the kinds of institutions that could assimilate $350 billion, at the lowest estimates, in reconstruction funds, which is twice pre-war GDP. Reconstruction at the lowest estimate is twice pre-war GDP, and that money is going to come in and not be stolen and disappear with the institutions they have now? I don’t think so. So you have got to build those institutions for that EU accession process in order just to assimilate the reconstruction funds properly. So that’s it. It’s not an uplifting story. But it is the story that’s on the table. And anyway, thank you for your attention.

There is also much more at the link. A lot of it is historical analysis that includes China. Whether you agree with Kotkin or not, I suggest you read the whole thing.

Kotkin’s analysis and the strategy he’s basing on it is fundamentally different from Charap’s. Kotkin is arguing that the Ukrainians should be supported as long as they want to keep fighting while at the same time they should be encouraged to think about what the post-war reality should be and how best to achieve it. For Kotkin that is Ukraine in the EU and with bilateral and multilateral security agreements with the US, various EU member states, and others. Ukraine absolutely defeating Russia is not one of Kotkin’s goals. From reading the rest of Kotkin’s speech, as well as the Remnick interview it is clear that Kotkin simply thinks Ukraine’s driving Russia out of all of the Ukrainian territory it is occupying and and imposing an unconditional defeat on Putin is improbable, not impossible. As such, his focus is on what gets Ukraine as much as possible. This is not what Charap is and has been arguing. Charap has been asserting, from several months before the genocidal re-invasion ever began, that Ukraine cannot win and should just capitulate to Putin’s demands through negotiations. Charap claims this is diplomacy. It is not. It is unilateral surrender. He also fails to recognize that the re-invasion is genocidal; that Russia’s Special Military Operation/Z War is a genocide.

I take Kotkin much more seriously than Charap and give the former the benefit of the doubt that the latter definitely does not deserve. However, they are both missing two important things. The first is that the war for Ukraine is an existential war. For Ukraine the outcome will determine if there is a Ukraine and what its future will be. Because Putin has made it clear that he and he alone gets to determine what Ukraine is, what it will be, and that if he is not allowed to do so then he will simply remove Ukraine and Ukrainians from existence. This does not mean that I think that Zelenskyy, Zalushnyi, Sirskyi, Budanov, and the other members of Ukraine’s national command authority will waste Ukraine’s blood and treasure by fighting to the last Ukrainian. However, it does mean they will prosecute the war for as long as they can in order to ensure Ukraine’s survival as a state, as a society, and as a culture. Only when they determine that their is no more benefit from fighting will they then negotiate.

The second, as I cited two nights ago, is Fiona Hill’s assessment that the war for Ukraine is the primary and largest kinetic portion of a world war.

“This is a great power conflict, the third great power conflict in the European space in a little over a century,” Hill says. “It’s the end of the existing world order. Our world is not going to be the same as it was before.”

Part of the problem is that conceptually, people have a hard time with the idea of a world war. It brings all kinds of horrors to mind — the Holocaust and the detonation of nuclear weapons in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the dawning of the nuclear age. But if you think about it, a world war is a great power conflict over territory which overturns the existing international order and where other states find themselves on different sides of the conflict. It involves economic warfare, information warfare, as well as kinetic war.

People worry about this being dangerous hyperbole. But we have to really accept what the situation is to be able to respond appropriately. Each war has been fought differently. Modern wars involve information space and cyberspace, and we’ve seen all of these at play here. And, in the 21st century, these are economic and financial wars. We’re all-in on the financial and economic side of things.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has turned global energy and food security on its head because of the way Russia is leveraging gas and oil and the blockade Putin has imposed in the Black Sea against Ukrainian grain exports. Russia has not just targeted Ukrainian agricultural production, as well as port facilities for exporting grain, but caused a global food crisis. These are global effects of what is very clearly not just a regional war.

Keep in mind that Putin himself has used the language of both world wars. He’s talked about the fact that Ukraine did not exist as a state until after World War I, after the dissolution of the Russian Empire and the creation of the Soviet Union. He has blamed the early Soviets for the formation of what he calls an artificial state. Right from the very beginning, Putin himself has said that he is refighting World War II. So, the hyperbole has come from Vladimir Putin, who has said that he’s reversing all of the outcomes territorially from World War I and also, in effect, World War II and the Cold War. He’s not accepting the territorial configuration of Europe as it currently is.

What we have to figure out now is, how are we going to contend with this?

It’s unlikely this ends in any satisfying way. You need every side willing to compromise, and Putin doesn’t want to compromise his goals.

Any compromise is, in any case, always at Ukraine’s expense because Putin has taken Ukrainian territory. If we think about World War I, World War II or the settlements in many other conflicts, they always involved some kind territorial disposition that left one side very unhappy.

There is not going to be a happy or satisfying ending for anybody, and it’s also not going to be happy or satisfying for Vladimir Putin either, honestly.

These excerpts from Hill’s interview really get to the heart of Kotkin’s strategic question regarding the post-war peace. Until or unless the US and our allies and partners are willing to actually accept that we are in a world war, that Putin started it but claims the US started it and Russia is the real victim, and that it started between ten and fifteen years ago we will never develop policies or strategies to effectively respond. Right now the US is proceeding under two different and competing policies. The first is the one that Kotkin refers to in his interview with Remnick: the US is not going to become directly involved and is moving cautiously for fear of triggering Putin into escalating the conflict. The second is Secretary of Defense Austin’s:

America’s goals for success [is that] Ukraine remain a sovereign country, a democratic country, able to protect its sovereign territory and that “we want to see Russia weakened to the degree that it can’t do the kinds of things that it has done in invading Ukraine.

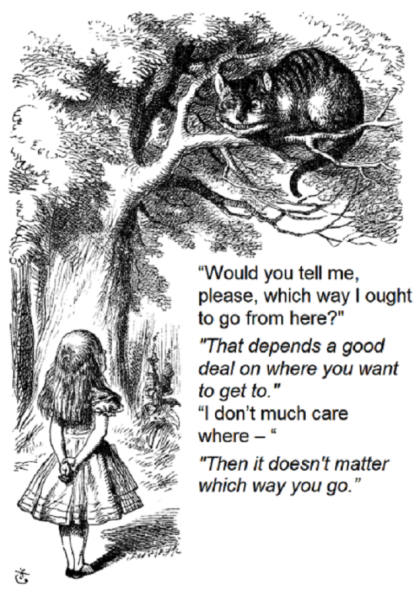

These two policy objectives are in direct competition. As such there is no way for the US, as the leader of the coalition supporting Ukraine, to develop strategies to both help the Ukrainians and to manage the post-war transition in order to secure the peace that are feasible, acceptable, suitable, and achievable. Until or unless the US national command authority is willing to admit that it is in a world war, that this world war has been going on for almost fifteen years and has largely been prosecuted using the elements of national power other than military power, and that it has to reconcile its two competing objectives of 1) not doing anything that would lead Putin to escalate, as well as potentially leading to Putin being overthrown or Russia coming apart during or after the war and 2) Russia being weakened so much that it can never do this type of thing again, then we are going to muddle along. This competing and oppositional strategic dynamic in the US has us existing in the Cheshire cat’s answer to Alice’s request for directions:

The important strategic concerns for the US are or should be:

- What does Ukraine want to do?

- How do we best support that?

- What is the US’s, as the leader of the coalition supporting Ukraine’s, policy and strategy to accomplish items 1 & 2?

- Is the policy and strategy feasible, acceptable, suitable, and achievable (FAS test plus achievability)?

- What is the strategy to both help Ukraine win the war in a way that establishes the conditions to secure the post-war peace, as well as to deal with the what the global system will look like post-war?

This is an existential war for Ukraine. If they lose they do not just lose on the battlefield, they lose the chance to determine their own future and, possibly, even to exist. It is an existential war for Russia because Putin has made it one in asserting that he and he along gets to determine Ukraine’s future and if it exists. It is imperative that our policies and strategies, as well as those of our allies and partners, center Ukraine as the primary actor. As such our strategic role is to focus on 1) what Ukraine wants to do, 2) what Ukraine can achieve, 3) what we can do to help Ukraine realize the second item on this list, 4) how we can help them secure the post-war peace so this does not and cannot happen again, and 5) what we need to be doing to shape whatever the new international system and global order arises out of the old one when this world war ends.

I’ll leave it there.

Kryvyi Rih:

This is how kids in Kryvyi Rih started their school year. In a bomb shelter. pic.twitter.com/E5wwSrxrUB

— Saint Javelin (@saintjavelin) September 1, 2023

Kharkiv:

Wonder why this boy covers his ears? He's afraid of loud sounds.

School year has started in Kharkiv metro.

📷 Gwara pic.twitter.com/4TrAm1Svjr

— Maria Avdeeva (@maria_avdv) September 1, 2023

Robotyne-Verbove:

The video was likely taken here in the circled area, in front of the possibly weaker section of the Russian main defence line.

During the last few days, no new geolocated material or other verifiable information has indicated major changes in the frontline. 2/2 pic.twitter.com/mhEgQ6cd1w

— Emil Kastehelmi (@emilkastehelmi) September 1, 2023

Velyka Novosilka:

VELYKA NOVOSILKA /1945 UTC 1 SEP/ UKR forces in contact at the northern limit of Zavitne Bazhanya. RU conducts fire missions up Mokri Yaly River Valley /T-05-18 HWY. Reports indicate a Russian Ka-52 helicopter was downed on the Zaporizhzhia axis, location to be determined. pic.twitter.com/sGUd2tqZ9p

— Chuck Pfarrer | Indications & Warnings | (@ChuckPfarrer) September 1, 2023

Kherson:

KHERSON AXIS /1730 UTC 1 SEP/ UKR forces conduct small unit crossing of Dnipro E of rail bridge- report the destruction of one RU high speed boat, one T-90N tank, one Masta-B howitzer and Ural fuel truck. UKR reports 17 RU casualties. pic.twitter.com/abJ66LW33Y

— Chuck Pfarrer | Indications & Warnings | (@ChuckPfarrer) September 1, 2023

These 11 children will start school year in Ukraine. They were kidnapped by Russian military, and now returned to Kherson. The youngest is just 2 years old. pic.twitter.com/fEMKZGKU1C

— Maria Avdeeva (@maria_avdv) September 1, 2023

That’s enough for tonight.

Your daily Patron.

A new video from Patron’s official TikTok:

@patron__dsns Згадую літо, а також вітаю усіх школярів та студентів з Днем знань!❤️

Here’s the machine translation of the caption:

I’m remembering the summer and congratulating all schoolchildren and students on Knowledge Day! ❤️

Open thread!

japa21

Great reading. You know, we know but most Americans don’t realize the fact that this is, in fact, an existential war for Ukraine nor that we have, as you say, been in a world war for over a decade. And I am not sure that most Americans would believe either or care about the former.

Adam L Silverman

@japa21: This is a significant part of the problem. Americans are still functioning within the Russian framing that they worked hard to seed and inculcate back between 2011 and 2014.

Mike in NC

The always unhelpful Trump toady Lindsey Graham has been telling the Ukrainians that they need to hurry up and hold new elections, because something something. Still waiting for him to be indicted in Georgia.

japa21

Going back to the 2012 campaign, everybody snickered when Romney said Russia was our biggest geopolitical enemy (including me). We should have listened.

Sparkedcat

Thank-you Mr. Silverman for this very informative update.

Adam L Silverman

@japa21: The problem is, even in hindsight, what the Russians were doing was so novel in the how that even those of us being paid to pay attention missed it until it became explicit in late 2013 and early 2014 in advance of the initial invasion of Ukraine.

Gin & Tonic

Thank you for highlighting these, Adam. As you know, I disagree that Kotkin believes Ukraine has agency, but I don’t think I have time this evening to go into this in detail. He’s just another in a long line of Western “experts” sitting on the sidelines, with no skin in the game, telling Ukraine what they should do.

Adam L Silverman

@Gin & Tonic: I think he does, but ultimately his concerns override that recognition.

Villago Delenda Est

As one of my battalion commanders once told the assembled command and staff group, a bad plan is better than no plan at all.

Carlo Graziani

Good analysis.

I often wonder why more senior US officials in DOD and the intelligence agencies don’t turn to US support of Afghan Mujjaheddin in the ’80s as a usable historical model. Afghanistan eventually turned into a chronic, bleeding wound that had a great deal to do with the endgame of the USSRs dissolution. To fail to see the parallel in Russia destroying its power in Ukraine, one must fail to also see that the threat posed by Russia to our institutions is analogous (in a minor key) to the threat posed by the USSR. And yet, all these people watched their TVs on January 6 2021. Who did they think was the ultimate sender and enthusiastic well-wisher of that fuck-you to our political order? Did Putin’s agency really never cross their minds?

gwangung

@Carlo Graziani: Maybe because power they can’t count in a spreadsheet and measure in terms of big KA-POWs isn’t taken as seriously by them?

oldster

To anyone who thinks that Ukraine should negotiate with Putin, I say:

Evgeny Prigozhin negotiated with Putin.

Villago Delenda Est

@oldster: What could possibly go wrong?

dr. luba

@oldster: Also, too, Budapest Memorandum.

Mike in DC

1. Push Russia out

2. Admit UKR to the EU

3. Provide interim security guarantees to UKR, pending NATO admission

4. Set preconditions for lifting sanctions–RUS recognizes international borders, ceases all hostilities, surrenders assets as reparations, returns all UKR pow’s and citizens, and submits to extradition of parties charged by the ICC.

Hey, if they don’t comply, enjoy endless sanctions, fellas.

YY_Sima Qian

A great read today Adam! Thank you!

I would have been sympathetic to Charap’s arguments about Crimea back in 2014. That the US has been far too reliant on sanctions as a foreign policy instrument, to diminishing or even negative returns, aimed to punish perceived bad behavior rather than incentivize a return to perceived good behavior, is not controversial & Charap is far from the only one making this argument. Even in late 2021 I thought Adam’s (& the Biden Administration’s) warning of an impending Russian invasion was alarmist.

However, the Russian conduct of the invasion has removed any doubt that Putin is exactly what Adam has said he is since 2016 & earlier.

I used to find Adam’s framing of the U.S. domestic political crisis a bit over the top, now I largely agree.

BTW, I find Kotkin to be good read on anything related to Russia & the USSR, but his China analysis is rather superficial, which is outside of his domain expertise. There is also an undercurrent of apologia for Western imperialism that I find very off putting.

frosty

This was one of the best posts you’ve written Adam. The perspective of winning the peace, securing Ukraine under different scenarios of how the war goes is something I haven’t read anywhere else. Thanks! And thanks for undertaking these nightly updates.

Slava Ukraini!

Adam L Silverman

@YY_Sima Qian: I am not a fan of sanctions. I do not think they work at all. I think we have decades of empirical evidence for this in regard to Cuba, the DPRK, and Iran.

Bill Arnold

Love the Alice/Cheshire cat image.

Kotkin is a bit glib, but at least it is (a description of) an actual analysis.

Fiona Hill also appears to be thinking clearly; was she always this way?

Your analysis is excellent; thanks for sharing!

I wasn’t really fully consciously aware of Russia’s information-warfare interference until roughly 2015 – it became increasingly difficult to ignore the malevolent influence activity directed against the USA .

I agree with Secretary of Defense Austin, and don’t much care if a major weakening of Russia leads to a bit of disassembly of the Russian Federation and some chaos. (We do need to avoid full-scale thermonuclear war. That’s a hard constraint.)

Adam L Silverman

@frosty: Thank you for the kind words. I’ve been working on this concept – setting the conditions on the battlefield to not just win the war, but secure the peace – since 2016. I did an assessment for XVIII Airborne Corps on this topic in regarding to Operation Inherent Resolve.

Adam L Silverman

@Bill Arnold: Thanks for the kind words. From what I know of Fiona Hill, yes, she’s always been this clear on this stuff.

Alison Rose

I find it repulsive when anyone not on the ground in Ukraine has the nerve to open their mouths about what Ukraine is doing wrong and what they ought to be doing, especially when “what they ought to be doing” translates to “placate the maniac so maybe he stops being so maniacal”. It has real shades of “maybe if you didn’t burn dinner, your partner wouldn’t beat you” and it’s equally disgusting. And the people like Vivek “I tried to be cool by rapping and Eminem told me to STFU” Ramaswamy saying “why don’t they just give up some of their land”, like…as Adam has said a million times, putin will not be satisfied with only some of Ukraine. He wants it all, or he wants to destroy it. And yeah, what if Canada had a stronger military than ours and suddenly decided they wanted Michigan and Minnesota and North Dakota. (Okay, they can take that last one.) Would all the GOPers and putin-fluffers in the US just be like “Eh sure, take what you’d like”.

This all just makes me so upset. Ukrainians are losing their homes and their limbs and their loved ones and their own lives and have been fighting harder than probably any country ever has for its own survival. Their leaders, not just Zelenskyy but of course especially him, have run themselves ragged every single day to protect their land and people, to get everything they possibly can to defend their country. They have been living through absolute hell, and all some people want to do is wag fingers at them and sit in their cushy offices and pontificate about what they ought to be doing, which is basically rolling over and licking putin’s boots.

Absolutely fuck that noise nine ways to Sunday.

Sigh. Україна переможе, damn it.

Thank you as always, Adam. Your analysis is so vital, and I’m always impressed that you manage to provide it without the 746 curse words I would include.

Anoniminous

Ukraine is not going to lose this war. If it ever looks like they will lose there is no doubt in my mind Poland would intervene. Poles hate, fear, and distrust Russia and have no wish to have a common border again.

The US’ fiddle-fucking around is only going to increase the butcher’s bill.

Another Scott

Meanwhile, … Reuters.com:

Good, good.

We need to give Ukraine everything sensible and possible to end the war quicker, and more lethal anti-armor weapons is part of that approach.

Slava Ukraini!!

Cheers,

Scott.

Chetan Murthy

https://nitter.net/IlvesToomas/status/1697500656825679955#m

Charap is a moral pustule. He defends moral imbeciles, incapable of making the right moral choices. The right thing to do with Russia is to wall it up, like North Korea, and let them fester. None of Russia’s neighbors who have escaped have anything other than hatred for them. Yeah sure #NotAllRussians. Sure. Sure.

Anoniminous

“The Treaty on Friendship, Cooperation, and Partnership between Ukraine and the Russian Federation was an agreement between Ukraine and Russia, signed in 1997, which fixed the principle of strategic partnership, the recognition of the inviolability of existing borders, and respect for territorial integrity and mutual commitment not to use its territory to harm the security of each other.”

source: Wikipedia

Russia is a Imperialist state and cannot be trusted.

Gin & Tonic

@Bill Arnold: As Adam says, Fiona Hill has always been perceptive and (IMO) correct.

Another Scott

Thanks for the nightly roundup, Adam.

I haven’t read the long posts you excerpt. I’m not sure it’s worth it for me.

My bottom line is similar to others expressed above:

Ukraine has agency here, and the post-war international order in Europe demands that it remain an independent state with secure borders. This war is about the future of the international order and international relations. It’s about Ukraine’s survival, but it’s also about the future of Europe and the world. Those who try to paint this as just some sort of border dispute, or it somehow being “pragmatic” and recognizing “facts on the ground” are ignoring what’s really at stake and are (effectively) propagandists for VVP and his fellow travelers. VVP changing borders by force invites the same in Serbia and lots and lots of other places…

It’s hard to see VVP being part of a permanent cessation of hostilities. His word is worthless. The war in Ukraine may not really end until VVP is gone.

It’s clear that VVP thinks he can wait Ukraine and the West out. I think he’s wrong, but the future is unwritten.

The West will have a large role in writing the future in Ukraine, through its military, financial, diplomatic, etc., support. Upcoming elections will have even more consequences than recently, and we need to keep pushing forward to accelerate progress.

The situation with Wagner in Africa, the spate of coups, etc., is another area that needs to get lots of front-of-mind attention. It’s clear to me that VVP is taking advantage of genuine and understandable discontent to stir up trouble there to bloody France’s nose, and make the US appear to be a less-than-reliable ally and friend. VVP’s “successes” there will make things more difficult elsewhere, so we need to be clear-eyed about what’s going on and figure out how to make democracies there more resilient. It’s another multi-decade task, of course.

My $0.02.

Cheers,

Scott.

Sister Inspired Revolver of Freedom

The Crimean Tatars would really, really like to enter the chat. Especially the ones still trying to live in Crimea. The Georgians currently fighting for Ukraine might also have a thing or two to contribute to the conversation. My disgust for so-called realpolitik & the “experts” who keep pushing its doctrines in the face of reality continues to intensify .

As always, thank you for your service, Adam. I’m glad you & the dogs came through the hurricane so well.

Slava Ukraini

Gin & Tonic

On another note, here’s video of one of russia’s IL-76’s being destroyed in Pskov. It was released by UA armed forces. So it appears that they used a drone to drop the explosives and had another drone filming. That level of intrusion is, how do you say, interesting.

Chetan Murthy

@Another Scott:

As do the CEE nations. The idea that they’re going to sit still for an armistice that allows RU to digest its winnings and rearm …. yeah no, that’s not happenin’. What’ll happen is that Poland, the other CEE nations, maybe Scandinavia, will form their own mutual-defense pact and turn into an armed camp. And I fully expect that they’ll go to war with Russia, b/c to do otherwise is to invite RU to rearm and defeat them in detail.

Charap is a fucking Russian asset: he’s counseling the *one* path that will certainly lead to more war.

Chetan Murthy

@Sister Inspired Revolver of Freedom:

Where was “realpolitik” when the Ottoman Empire was being taken apart? Or the Austro-Hungarian Empire? Or Germany? Nobody said “oh, we need to preserve Germany’s sphere of influence” — they said “we need to defang Germany so they can never endanger their neighbors!” They didn’t say “gosh, we need to help the Austro-Hungarian/Ottoman Empire to get back on its feet, re-establish its traditional sphere of influence and authority”; they said “they’re doomed, let’s carve the fucker up!”

That’s what real “realpolitik” is: the beast is dying, and we’re the ones with the knives, let’s carve the fucker up.

These IR “realists” are indistinguishable from Russian assets.

NotoriousJRT

I could barely breathe while reading the Kotkin speech.. It struck me as the cold-hearted and tragically clueless jackassery of outside corporate consultants sent into a company to fix it by killing it – with absolutely no skin in the actual game, even reputational, IMO. As I have admitted before, I have no expertise in the areas critical to evaluating where all this all is going. But, I could not stand the analogy of the Ukrainian vs. Russian houses. Does he really think that given its territorial “inch,” (or foot or yard) that Russia will not forever keep seeking its “mile”? His entire conception of winning the peace is rooted in concession to Russia – bowing to the stronger party and admitting weakness. There can be no NATO for Ukraine only security agreements that may be meaningless soon after their execution. He had me wanting Ukraine to retake Crimea and deal as harshly as possible with the Russians that Kotkin implies will comprise 100% of the population remaining. I don’t think anything I’ve read here through 555 days of updates has made me feel more depressed. Thank dog for Patron.

dnfree

@japa21: I am far from a foreign policy expert, but when Romney made the comment about Russia I thought he had a point. The instant mockery seemed just reactive, not thought through.

JR

@Chetan Murthy: there is a precedent for the “realist” view e.g. Metternich

Sister Inspired Revolver of Freedom

@Chetan Murthy: Totes agree!😡 The lack of historical knowledge & context these people display never ceases to amaze me in the worst way possible. If I, a faux amateur historian at best, can see the folly of the suggested “negotiations” what are these people even doing opening their mouths & opining while real people lose their land, homes, infrastructure, futures, those they love &, oh, yeah, their lives. They are dancing on Ukrainian graves & it needs to stop! Defeat Russia, then let’s talk.

Chetan Murthy

@NotoriousJRT: I share your anger and frustration. 100%.

I think it’s still useful to work thru Kotkin’s position. He’s *assuming* that Ukraine will benefit from what South Korea (and West Germany) got: the US and other allies basically setting up a massive armed camp to oppose their adversary. That’s a *massive*, *massive* assumption, that you certainly can’t take for granted today! And I’m angry and disappointed that he didn’t at least *acknowlege* it — he’s an academic and a historian, esp. of the Cold War, and he doesn’t get a pass for skipping past it!

There’s a reason we need to aim for Russia to fucking *collapse*: because we have no guarantee that Ukraine’s allies will be around for the long haul. So we’d better make sure RU can’t threaten Ukraine (and Europe) for a long goddamn time.

Adam L Silverman

@Another Scott:

Our Africa policy is all over the map. It isn’t coherent and hasn’t been, regardless of administration, for decades. As a result, we have already lost over a 1/3rd of Africa to Russian subversion. Given the policy incoherence, I highly doubt we have a strategy, let alone a plan, to prevent the subversion of the rest of the African states and societies.

wjca

Given his background, it would be totally unsurprising if Putin thinks of them explicitly as “useful idiots.”

Ken B

@Villago Delenda Est: Negotiating with Putin is like negotiating with a hungry shark, except sharks don’t lie.

Jay

I laugh at the idea that Ukraine is going to have to “deal with” an insurgency in de-occupied territory.

Chetan Murthy

@Jay: There are no *men* left there. Soon there will be no boys, and soon after that, no women. RU is killing them all: those who aren’t tortured/murdered, are sent to the trenches where they die of either bullets in the front, or bullets in the back.

Lyrebird

@Jay: I do suspect that a restored, free Ukraine will have an eastern edge with lots of heartache and mistrust. I vaguely remember Adam talking about the formal side: how will the Ukrainian government treat families where the men fought for the DPR, things like that.

But the way that author up there talks about Crimea? What

@Sister Inspired Revolver of Freedom: said… no mention of Tatars, no acknowledgement of the damage that was already done 2014-2022. I noticed that not only has Putin managed to kill off many Tatars by sending them into this war, the child labor place is in their relocated territory, too, unless I misread.

Sally

When the experts talk of an armistice like Korea as being an acceptable solution to war, I wonder if anyone thinks that the North Koreans would agree. Do the North Koreans, who are separated from family, dying, starving, immiserated and watching their children, grandparents starve and die think they got a good deal? At the hands of an extremely wealthy, privileged totalitarian elite. I so want to ask Kotkin this question. Was the Korean armistice a good deal for the North Koreans? And do they count?

Putin, and Russia, don’t want to rule over Ukraine benignly, they want to eradicate it, to torture and forcibly deport and Russify Ukrainians, usurp land and resources, and settle Russians there. Would an armistice look like a good deal for the occupied population? This is not even the same as Korea, it is worse.

Am I wrong? Or are these many highly paid experts idiots?

Chetan Murthy

@Sally:

You’re not wrong, but they’re not thinking about this in terms of morality. They’re thinking about this in terms of achievable outcomes, economics, and geopolitics. I agree with you, but we don’t need to insist on morality (and heck, it’s possible we’d be wrong: look at what we’ve done all over Latin America and the Middle East). We can stick to the ground that Kotkin and Charap choose, and they’re *still* wrong. B/c a durable peace, a peace that Kotkin would classify as “winning”, is not one where RU is allowed to come away thinking it won. RU needs to be beaten to a bloody pulp, hopefully fall apart into many smaller states, in order that it can no longer threaten its neighbors, and thereby, produce a “winning peace”.

As long as RU remains this gynormous bear, constantly attacking its neighbors, we’ll never have peace in Eurasia.

wjca

Put it another way: why would the Ukrainians want to be like to Tibetans or the Uyghurs? Because that, more than North Korea, is what Putin envisions.

Chetan Murthy

@wjca: Or the Circassians. Or the Chechens. Or the Estonians. I don’t know how many other peoples were ethnically-cleansed to within an inch of national extinction by the Muscovites.

This is what Muscovy is, what Muscovy does. They’re genocidaires, and have been forever.

Fair Economist

There’s no negotiation with Putin. He can’t be trusted on anything. Ask Prigozhin, oh wait no you can’t anymore, because you can’t trust Putin. After Putin? We’ll have to see. He might be replaced with somebody just as bad, in which case nothing really changes, or maybe his replacement could be trusted to honor at least some deals. We can’t know until he’s actually replaced.

I have no idea how Kotkin come up with the fantasy that Xi would ruler-slap Putin if he broke a Chinese brokered agreement. Xi wouldn’t care, unless somehow it damaged real Chinese interests, and in that case he would care regardless of who brokered it.

Fair Economist

@Sally: You are 100% right. We took the Korean split because we had to – we could not dislodge the Chinese. If, with all the aid the West can provide, Ukraine can’t expel the Russians, then a partition will happen because it has to. That’s a decision for the Ukrainians to make.

BethanyAnne

Adam, thank you for all your work here, but this especially.

Sally

@Chetan Murthy: I don’t believe I am thinking of this in terms of morality, but in Kotkin’s terms of human suffering. To minimise human suffering we have to evict Russia from Ukraine. All these other examples, from wjca and Chetan Murthy, justify my point, to my mind. In terms of morality, the answers are pretty cut and dried, but in pragmatic terms I can see there is room for thoughtful debate. But looking at further examples where the invading regimes have remained, and after some consideration for the suffering in both scenarios, I think the answers are still pretty cut and dried. Would more people suffer, and more die, if Ukraine surrendered to Russian rule? They might be different people, but many, many, would suffer and die. Many Koreans (and Americans) would have died had that war continued. Many Koreans have died since the end of that war, and suffered, and are suffering and dying still.

It’s a big risk to think that “West Ukraine” would be a European version of South Korea. Especially in the potentially low growth, climate challenged world we are entering this century, rather than the high growth, post WWII world of the ’60’s on.

I’m probably just exhibiting my ignorance on all this, but just my opinions after all this reading and thinking.

wjca

The critical difference being that Russia simply doesn’t have the manpower that China had available. Not to mention having an economy which was in tatters even before the invasion. (A Russian moon shot crashing while an Indian one landed successfully is telling. Russia has vastly more experience and infrastructure than India when it comes to space flight and spacecraft. But the condition of that infrastructure, especially after a quarter century of kleptocracy, is questionable.)

BSChief

@wjca: The Tibetans and Uighurs both are entirely within China’s borders and control. An armistice between Ukraine and Russia would leave significant Ukrainian territory under Russian control; the plight of Ukrainians in that territory would be very similar, if not worse, to the conditions faced by Tibetans and Uighurs. However, most Ukrainians would remain outside Russian control. As far as comparisons to Korea go, I believe the Korean Armistice line that persists today is pretty close to the prewar boundary, unlike any boundary that would currently exist under a Russia/Ukraine armistice.

@wjca:

BSChief

I do believe that Putin aspires to have all Ukrainians in the same position vis-a-vis Russia that the Tibetans and Uighurs are in vis-a-vis China.

Sally

@Fair Economist: I think the other aspects to Korea were that Americans were dying in Asia, in a war many Americans were not invested in. It was very soon after the tragedy of WWII. Political pressure from Americans who didn’t want their sons dying half a world away contributed to the armistice.

The Ukraine war is quite different in these respects. Also UA has significant support from much of Europe that sees the danger of territorial surrender to Russia. Ukrainians are doing the fighting and dying. So far they are willing to continue to do this. They are asking for ammo, not armies.

Russia today is all quite different from China of the 1950. China was not fighting a clandestine global war like Russia is today. No cyber war, no economic war, no information war. The United Nations was a nascent organisation with only about 50 or so members. It was a different world.

Ksmiami

@Chetan Murthy: completely- and break their ability to trade internationally too. Fuck Russia- the country needs to be sealed up.

Betty

@Anoniminous: Why do so many retired military leaders see this while the current ones do not? I just saw General McCaffery (sp?) complain about this reluctance to send the necessary weapons.

ginkgo

Adam,

Thank you very much for these these posts. I have read almost all of them and the ones I didn’t read were due to not having time to even look at a computer except for work.

This particular post seems to summarize (at least to me) most of the underlying ideas of when this started, what is going on now, and where this conflict may go.

You bring up concepts that I never even considered and have opened my eyes about Russia’s war with us. I remember the first time you spoke of this and it totally changed my view of the last few years.

I just want you to know how much these posts and the other readers’ replies have helped my understanding about this war and just how much they are appreciated.

Hope you see this since it is Saturday morning.

wjca

Also, South Korea was, historically, a rural backwater. Northern Korea was, pre-war where all the industry was. So all military (and support) equipment had to be imported. Mostly across the whole Pacific. Ukraine needs advanced equipment, and ammo. But it has the basics. And the know-how to build more. They’re also working of building the capability to build some more advanced equipment themselves.

Ixnay

@Adam L Silverman: As always, many thanks for the work you do on this. Apropos of the African cluster fck, I caught this radio show on Thurs. The speaker was just awesome. I just found it on line to stream. Might be of interest to the security minded jackals.

https://www.mainepublic.org/show/2-pm-public-affairs-programs/2023-08-28/speaking-in-maine-mid-coast-forum-on-foreign-relations-ambassador-charles-ray

He begins with the evolution of humans and rolls to the present. Seriously good.

Chetan Murthy

Phillips P. O’Brien about the future of NATO, in a time of wavering US committment: https://nitter.net/TheAtlantic/status/1697984000046883109#m

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2023/09/europe-united-states-international-relations-decoupling/675211/?utm_campaign=the-atlantic&utm_content=true-anthem&utm_medium=social&utm_source=twitter

Another Scott

@Ixnay: Thanks for the pointer. It’s appreciated.

Cheers,

Scott.