I’ve mentioned now and then that I’m working on a video game with a friend. It’s an adventure game/dating sim with a modern Lovecraftian setting, probably called “Starspawn: A Miskatonic Mystery”. We’ve successfully launched board and card games in the past, but we’ve only ever made toy computer games, so we aren’t total noobs but it’s still shaping up to be a real journey. From scripting to engine development to finding artists to work with, it’s been really great learning all the tricks of the trade, though it’s been less fun internalizing the well-known fact that game development is harder than you think. And it’s going pretty well, thank you for asking! We have most of the functional requirements down and are stapling everything together, skinning it, making it Feel Like A Game, etc. I also haven’t written more than an outline past Act 2. So, 90% of the work is done, we’ve just got the other 90%. And then we can do a Kickstarter with a playable demo. Anyway…

Part of the gameplay is inspired by the old LucasArts puzzlers like Monkey Island. You know—click on stuff to interact, get witty banter, maybe add it to your inventory. Apply items to other items or to somewhere else on the screen, witty banter, maybe something happens.

(This new Monkey Island game is a blast, by the way, if you’re looking for something to play.)

Coding up this part of the engine was pretty straightforward. What’s been much tougher is learning how to write fun puzzles! Last year I was talking about this with a friend who makes augmented-reality games as a hobby and he introduced me to a concept that Ron Gilbert (the grandpappy of these games) came up with at LucasArts: the Puzzle Dependency Graph. This is a super interesting tool and I thought I would share it with you all. Part flowchart, part mathematical construct (you can calculate metrics from it)… It’s not just useful for writing puzzles; I’ve found it to be helpful in plotting out the actual mystery too.

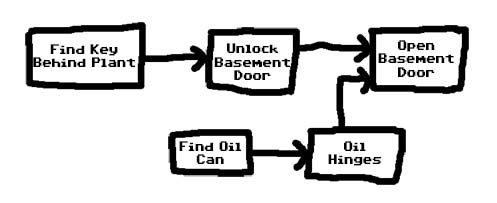

I’ll be stealing some images from Ron Gilbert’s blog post on the topic. Here’s his example for a very simple puzzle, where your goal is to open the basement door:

I always work backwards when designing an adventure game, not from the very end of the game, but from the end of puzzle chains. I usually start with “The player needs to get into the basement”, not “Where should I hide a key to get into some place I haven’t figured out yet.” […]

So… first, we’ll need figure out what you need to get into the basement… And we then draw a line connecting the two, showing the dependency. “Unlocking the door” is dependent on “Finding the Key”. Again, it’s not flow, it’s dependency.

Now let’s add a new step to the puzzle called “Oil Hinges” on the door and it can happen in parallel to the “Finding the Key” puzzle…

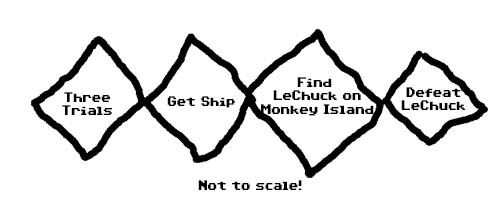

The end goal is a series of act-sized diamonds:

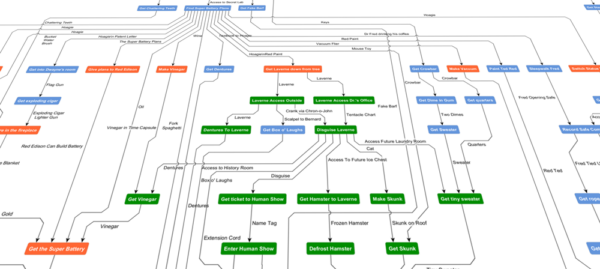

In an adventure game, providing a fan-in/fan-out shape like this is very important. It allows the player to work on things in parallel, if they get stuck on any particular sub-puzzle; and, if you’re doing a branching-narrative thing, can provide both choice (or sometimes the illusion thereof) and structure for plot-driven stories. So, in addition to being a useful way to map out what you’re doing, it can also let you know, at a glance, whether you’re doing it right, and how complex any given section will be for the player. For a real-world example, here’s a slice of Day of the Tentacle, from a talk excerpt that goes into some of the mathematical concepts you can apply to the graph, if you are interested in that:

In an adventure game, providing a fan-in/fan-out shape like this is very important. It allows the player to work on things in parallel, if they get stuck on any particular sub-puzzle; and, if you’re doing a branching-narrative thing, can provide both choice (or sometimes the illusion thereof) and structure for plot-driven stories. So, in addition to being a useful way to map out what you’re doing, it can also let you know, at a glance, whether you’re doing it right, and how complex any given section will be for the player. For a real-world example, here’s a slice of Day of the Tentacle, from a talk excerpt that goes into some of the mathematical concepts you can apply to the graph, if you are interested in that:

In puzzles and stories, your characters obviously have to do some things before they can do other things. You can expand each of those things into a sub-graph of other things, or collapse them, as necessary. If you want to give the players more time with something, or expand complexity in any given area, you can simply choose a node and expand it into another diamond. For example, in the newest Monkey Island game, at one point you need a mop. You could just have the character ask the right guy for a mop. But the game instead has you ask the guy for a mop–and then he sends you on a quest to find the “mop handle tree”, which is in a secret place, which requires you to find a map for it, but the cartographer needs something else…

Or suppose there’s a hole in your novel where act three should probably be; the hero goes from point A to point B with minimal trouble. This is immediately visible on your graph. So you take the one node, “gets to point B”, and branch it out. Maybe the road they need to take is closed, so they need to take a detour. Okay, so they have to figure out which detour to take. They pull up Google Maps on their phone–

Okay, so Google hasn’t mapped this area, so they find the nearest gas station–

Okay, so it’s a spooky gas station abutting the woods. The attendant tells them–

The attendant won’t tell them, because…

You get the idea. I’ve used it to map the actual mystery plot of the game too, and it’s been very helpful, especially for keeping track of the things that are happening offscreen.

So what’s everybody playing these days? I’ve got Monkey Island to finish, and some dating sims for research (Coming Out On Top and Monster Prom), and like many I am still chewing my way through Baldur’s Gate 3… and finishing Persona 4… I play a lot of games. Finally beat Metroid Dread, that was very fun.

Writing Puzzles (video game open thread)Post + Comments (52)